The Minimal Methanol Economy: Frequently Asked Questions

Table of Contents

- 1. What is a "minimal methanol economy"?

- 2. Is green hydrogen still needed in a "minimal methanol economy"?

- 3. How sustainable is the biomass used to produce the methanol in your scenarios?

- 4. Isn't straw used for animal bedding, animal feed, mushroom cultivation or returned to the fields to enhance soil carbon?

- 5. What is e-biomethanol?

- 6. Why is direct air capture (DAC) not used?

- 7. What does the carbon cycle look like?

- 8. Wouldn't first generation biofuels like renewable/biodiesel or corn ethanol be better?

- 9. Given recent biofuel fraud, how to you guarantee the sustainability of wastes and residues?

- 10. Is (e-)biomethane not a better solution than (e-)biomethanol?

- 11. Can't e-biomethane be liquefied to gain similar advantages to e-biomethanol?

- 12. Aren't the costs of keeping the existing methane transmission network small?

- 13. How would end-consumer prices of green methanol differ from hydrogen or methane?

- 14. Wouldn't the large-scale use of methanol require methanol pipelines?

- 15. Are CO2 pipelines required in the scenarios?

- 16. Are the logistic costs of transporting biomass and biogas included in the model?

- 17. Why is the minimal methanol scenario more expensive?

- 18. Are there resilience benefits to using methanol (e.g. dealing with shocks better, losses of pipelines)?

- 19. Is the Allam cycle generator required in order to close the carbon cycle for the scenario?

- 20. How easy is it to retrofit an existing gas turbine to use methanol?

- 21. What is the typical size envisaged for a methanol synthesis plant? How many would be needed in Europe/Germany?

- 22. How would methanol be transported away from each methanol plant?

- 23. How would existing biogas units fit into the minimal methanol economy?

- 24. How would existing bioethanol and biodiesel plants fit into the minimal methanol economy?

- 25. How would the results change if a lot of carbon sequestration or cheap carbon dioxide removal were available?

- 26. Isn't it always cheaper to sequester a tonne of carbon dioxide than to use it in a fuel?

- 27. What is the carbon dioxide abatement cost of e-biomethanol?

- 28. What path dependencies are locked in by pursuing e-biomethanol?

- 29. Path to climate neutrality: could you start producing (e-)biomethane, then switch to (e-)biomethanol later?

- 30. Do any e-biomethanol plants exist today?

- 31. Who would the first users of green methanol be?

- 32. What provides industrial process heat in the model?

- 33. There is significant methanol usage even in the reference cost-optimal case - aren't all the scenarios methanol scenarios?

- 34. What if green methanol were imported?

- 35. Which technology innovations would improve the case for a minimal methanol economy?

- 36. Which technology innovations would worsen the case for a minimal methanol economy?

- 37. Is methane/hydrogen value chain leakage an argument for methanol?

- 38. Is there any similarity with cellular approaches for energy supply?

- 39. How flexibly must the electrolysis and methanol synthesis be operated?

- 40. How are agriculture and forestry affected by the "minimal methanol" concept?

- 41. Could more CO2 be captured and cycled back to methanol production?

- 42. Could CO2 be exported for methanol synthesis outside of Europe at sites with cheap green hydrogen?

- 43. How are steel and ammonia produced in the model?

- 44. Aren't ammonia, LCH4, LH2, ethanol, LOHC, DME, or Fischer-Tropsch fuels better than methanol as an energy carrier?

First Posted: 2025.07.07, Last Revised: 2025.08.04, Author: Tom Brown

This Frequently Asked Questions page answers common questions arising from our 2025 paper The Minimal Methanol Economy as a Gap-Filler for High Electrification Scenarios (see this blog post for an introduction to the paper).

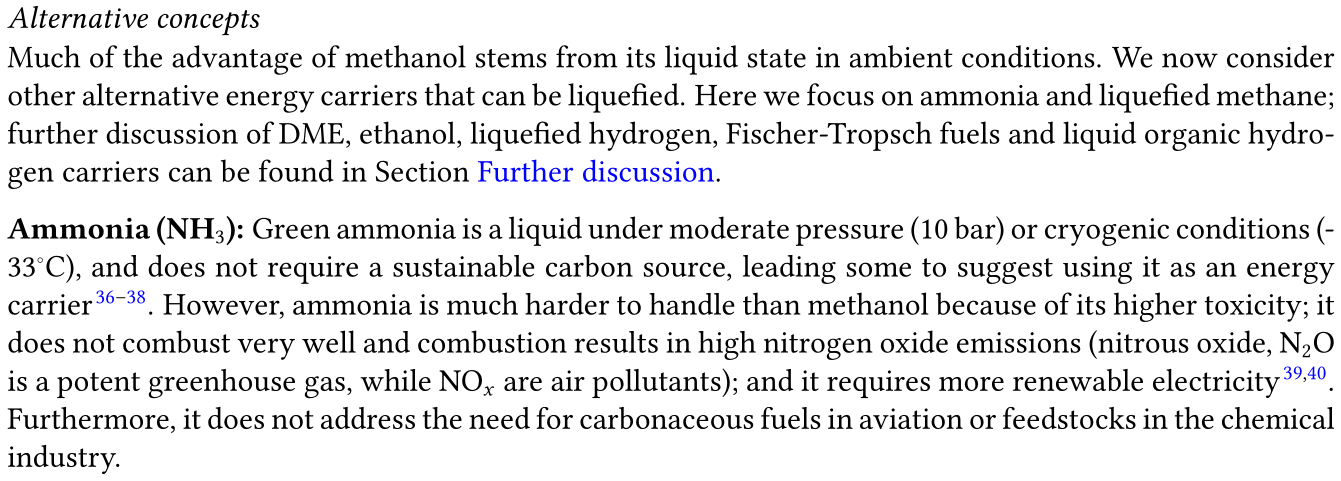

1. What is a "minimal methanol economy"?

The basic concept is described in this blog post:

The Minimal Methanol Economy as a Gap-Filler for High Electrification Scenarios

but to keep it short: "electrify as much as possible and use methanol for the rest".

In contrast to a "hydrogen economy" this minimises molecule use and avoids transporting fiddly gases; any green hydrogen stays inside industry clusters that produce green methanol, ammonia or steel. Pipeline transport and underground storage of hydrogen are avoided.

In contrast to a "methanol economy" (suggested by Fred Asinger, George Olah and others), we suggest to keep methanol usage to a minimum and e.g. avoid applications in land transport and heating that can be electrified. We also avoid fossil production of methanol.

Methanol is used for non-electrified shipping, producing kerosene for long-distance aviation, plastics, and for backup power and district heat when other renewable sources are absent. Methanol is easy to transport and store since it is a liquid at ambient conditions.

The volume of green methanol needed depends how much carbon can be sequestered, how much can be electrified, and how demand changes.

2. Is green hydrogen still needed in a "minimal methanol economy"?

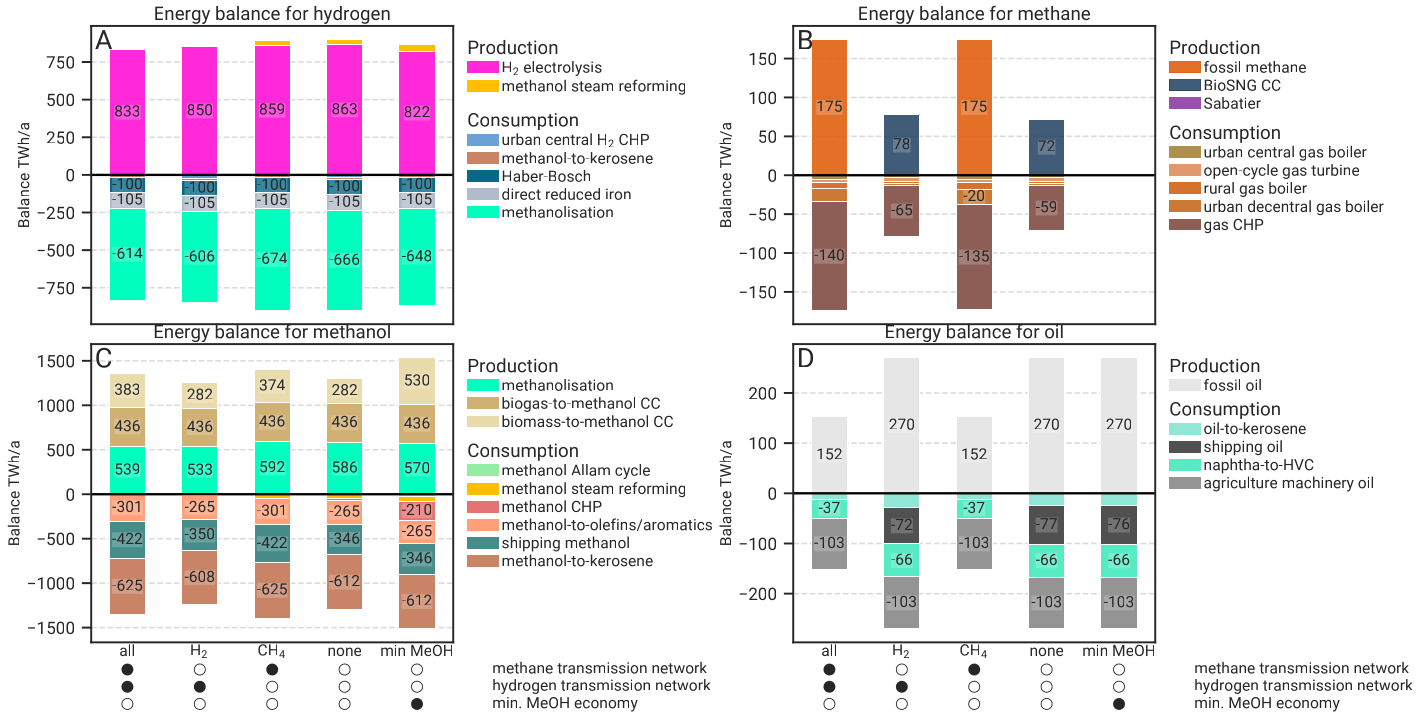

In the default setup, where only 200 MtCO2/a sequestration is allowed in Europe in 2050, there is around 820 TWh/a of electrolytic hydrogen production:

Figure 1: Energy balances for the default scenario with 200 MtCO2/a sequestration.

This hydrogen is all used locally inside industry clusters to produce the following green derivatives: methanol (using excess CO2 from biomass), ammonia (using nitrogen from the air) and steel (using imported iron ore).

As discussed below, if the sequestration is increased, the model prefers to compensate fossil fuels with carbon dioxide removal (CDR) using the biogenic carbon for sequestration instead of in fuels.

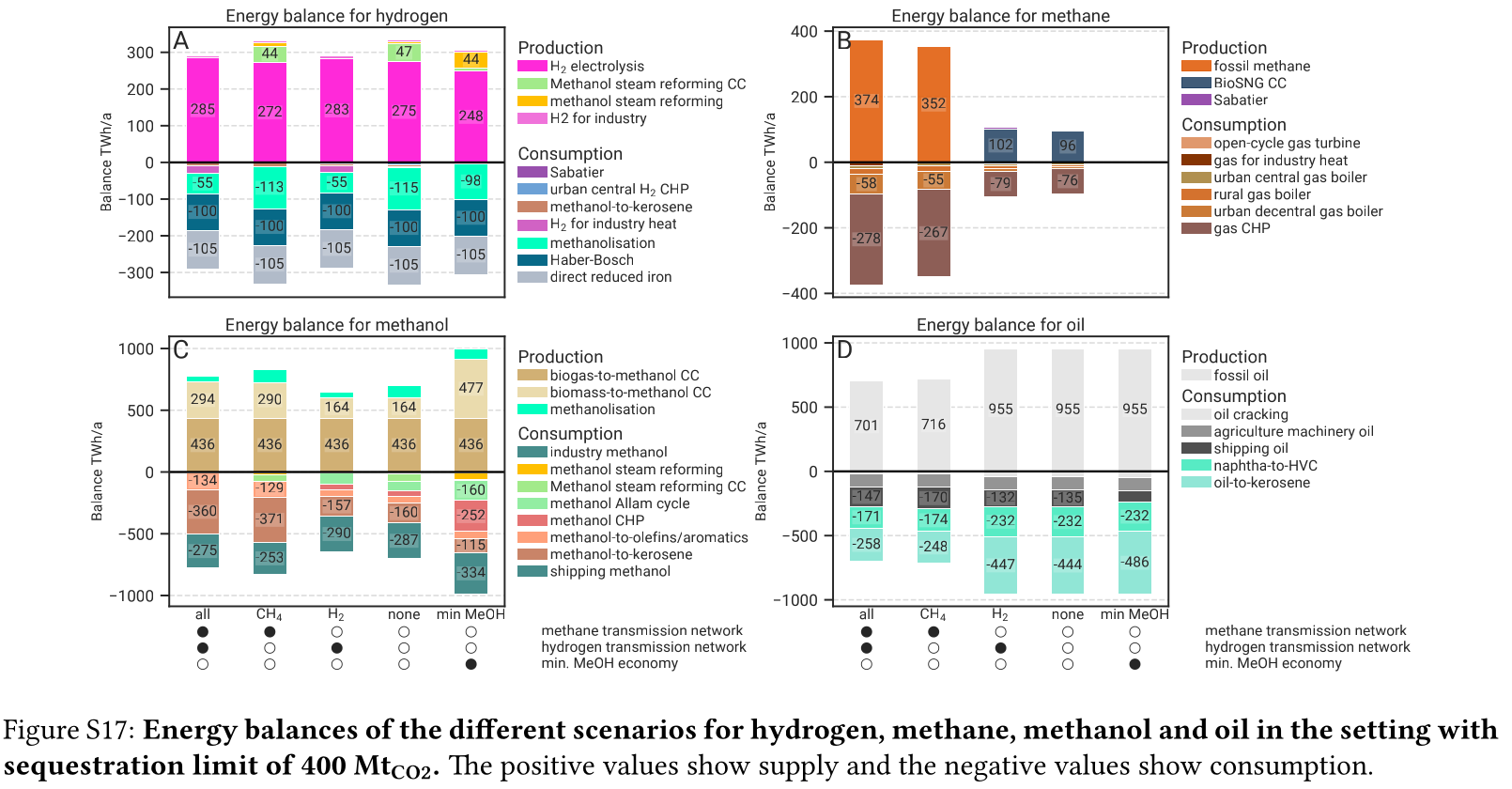

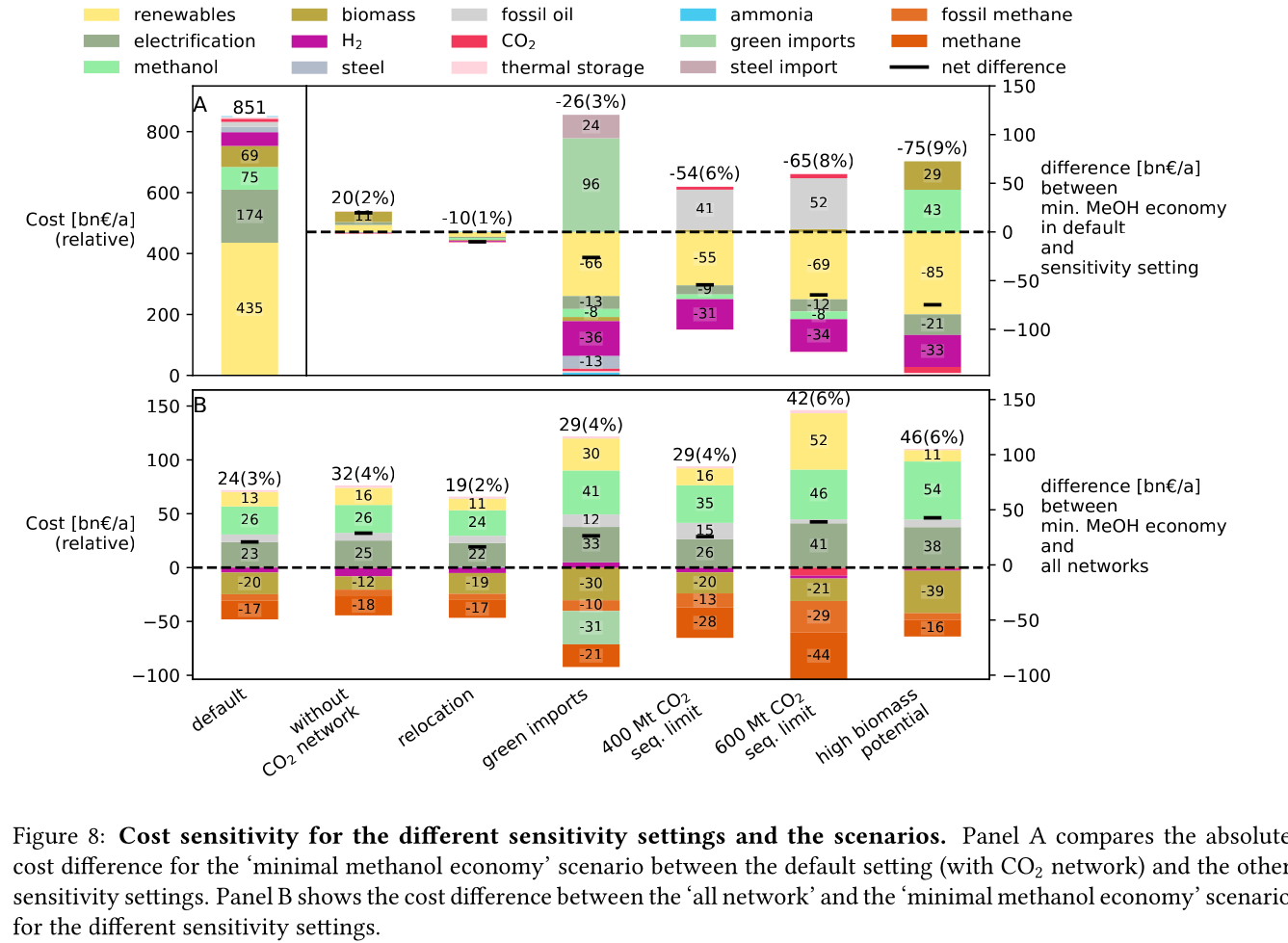

At 400 MtCO2/a sequestration the use of electrolytic hydrogen drops to 250 TWh/a:

Figure 2: Energy balances for sensitivity with 400 MtCO2/a sequestration.

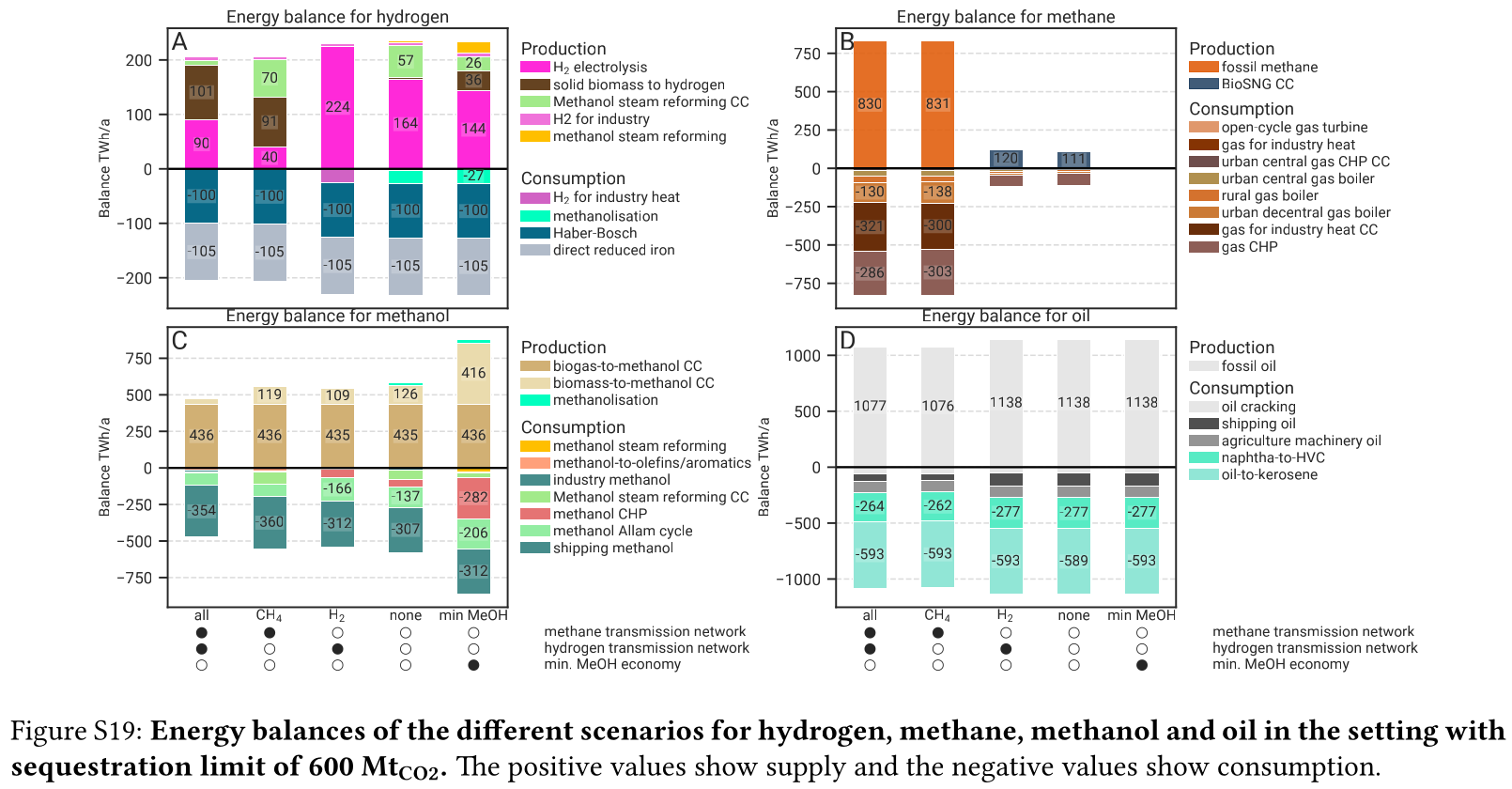

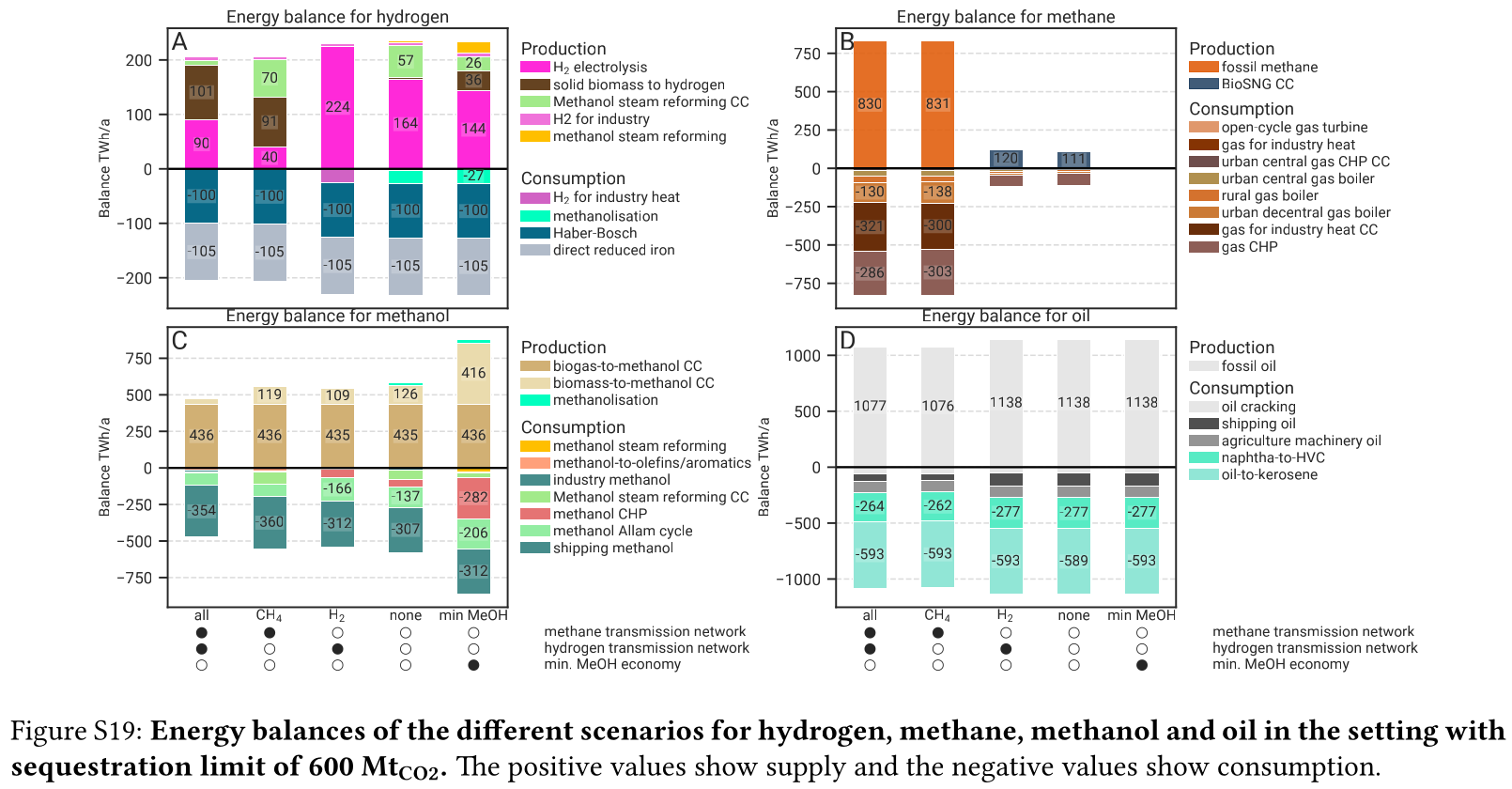

At 600 MtCO2/a sequestration it drops to 145 TWh/a:

Figure 3: Energy balances for sensitivity with 600 MtCO2/a sequestration.

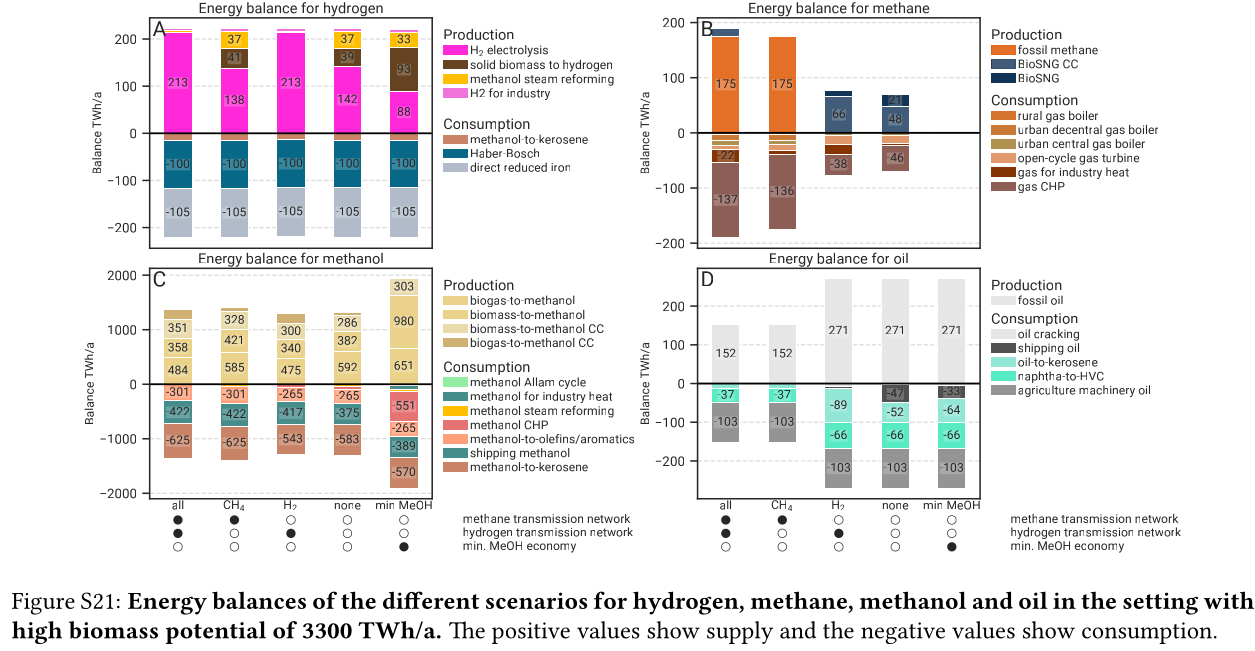

Similarly, the scenario with higher biomass potentials also allows to avoid most electrolytic hydrogen:

Figure 4: Energy balances for sensitivity with more than double the biomass potential (3300 TWh/a).

3. How sustainable is the biomass used to produce the methanol in your scenarios?

Biomass is used to produce methanol in our scenarios. Since biomass has excess carbon compared to methanol, the additional carbon can be upgraded with electrolytic hydrogen to make the most of the available carbon, so-called e-biomethanol. This allows the model to avoid expensive direct air capture (DAC).

Only sustainable biomass sources are allowed in the model. This means the model is forced to used wastes and residues that do not cause any additional land use. In particular, dedicated energy crops such as corn/maize, other cereals or rape seed, are not allowed. This would be a substantial change to the biomass substrates used today.

The biomass sources are split into two categories: solid biomass and biogas. Solid biomass can be combusted for process heat or power generation, or gasified to produce synthetic fuels. Biogas sources can be processed in anaerobic digestors into biogas (a mixture mostly of methane and carbon dioxide, assumed in the model to be 60% methane and 40% carbon dioxide by volume). The boundary is fluid; some solid biomass could be used in biogas units (for example, Millinger et al, 2025 also allow straw to be mixed into the biogas substrate).

For the European area using wastes and residues from the JRC's ENSPRESO dataset (medium potential) this translates in 2030 to 1049 TWh/a of solid biomass (coming from agricultural residues like straw, forestry residues, sawdust, biogenic municipal waste) and ~342 TWh/a of biogas (from animal manure and sludge waste).

Focusing on Germany, there is 189 TWh/a solid biomass and 32 TWh/a biogas.

Further sustainable biomass could be leveraged without increasing land usage by allowing to use cover crops (crops planted between growing seasons to maintain soil integrity) or grasses on marginal lands.

Short rotation coppices are not included but are a good example of crops that need land, but provide a high carbon yield, while avoiding soil disturbance and enhancing biodiversity if planted appropriately.

4. Isn't straw used for animal bedding, animal feed, mushroom cultivation or returned to the fields to enhance soil carbon?

The JRC ENSPRESO dataset takes into account alternative uses of each residue and waste. Only around one third of straw is available for energy (in the medium scenario). The rest is used for animal bedding, mushroom cultivation, or returned to carbon-poor soils. Use of straw for animal feed is rare.

5. What is e-biomethanol?

Biomethanol is methanol produced exclusively from biomass. Since biomass has an excess of carbon compared with methanol, the excess carbon can be used with added electrolytic hydrogen to enhance the yield of methanol for a given mass of biomaterial. If e-hydrogen is added, the resulting methanol is called e-biomethanol to indicate its mixed origins (all carbon from biomass, some hydrogen from electrolysis).

The addition of e-hydrogen makes sure all the carbon in the biomass is utilised; repeated scientific studies show that the sustainable carbon in biomass is of more importance than its energy content (Millinger et al, 2025). E-hydrogen tends to be expensive, so e-biomethanol is typically more expensive than biomethanol (e.g. 160-180 €/MWh versus 80-110 €/MWh for the 2030+ time horizon).

6. Why is direct air capture (DAC) not used?

Direct air capture (DAC) refers to technical measures to extract CO2 from the atmosphere, where it is present at low concentrations. DAC is implemented in the model, however the cost of CO2 capture from the air is significantly higher than capturing CO2 from biomass (for 2050, roughly 300 €/tCO2 versus 100-150 €/tCO2). As long as biogenic sources are available, the model prefers biomass to the air as a source of carbon.

The broader logic is that if the plants are already extracting CO2 from the air for food and our building materials like wood, we can use the excess CO2 in biogenic wastes and residues for plastics and energy.

DAC also has a long path ahead of it before it can scale up to a megaton per year, let alone the gigaton per year scale needed (Brazzola et al, 2025).

7. What does the carbon cycle look like?

In the minimal methanol scenario, the 1391 TWh/a of biomass contains around 114 MtC/a (equivalent to 417 tCO2/a).

1211 TWh/a of this is used to make methanol (99 MtC/a, 363 MtCO2/a).

The rest goes to industry heat, where some carbon is captured.

Extra carbon is also captured from the Allam cycle plants, waste-to-energy plants and industry heat with carbon capture (? MtC/a, ? MtCO2/a).

1500 TWh/a of methanol is produced (the extra energy coming from electricity and 648 TWh/a of hydrogen), which has 102 MtC/a (372 MtCO2/a).

This carbon is then released into the atmosphere when used in planes and ships. Some carbon is captured from methanol use in Allam cycle plants, burning the resulting plastics from MtO/A in waste-to-energy plants and industry heat.

TODO: Sankey of carbon.

8. Wouldn't first generation biofuels like renewable/biodiesel or corn ethanol be better?

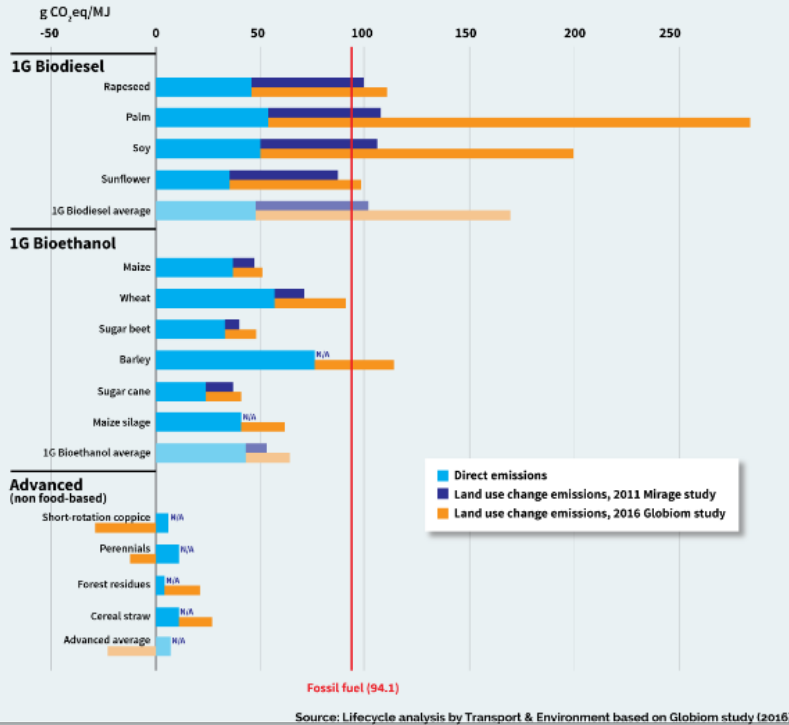

Most of the biofuels today come from dedicated energy crops that require significant amounts of energy, fertiliser and land. Including the indirect land use change that comes when food crops are displaced, forcing food to be grown on virgin land elsewhere, can make the life cycle greenhouse gas balance of some biofuels worse than fossil gasoline or diesel.

Figure 5: Lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions for different biofuels (source: Transport & Environment, 2016)

There are some limited biogenic wastes that could use routes other than methanol, e.g. used cooking oil via the HVO route to diesel or kerosene.

Research on life cycle emissions of biofuels:

- Searchinger et al, 2008: "Use of U.S. Croplands for Biofuels Increases Greenhouse Gases Through Emissions from Land-Use Change"

- Lark et al, 2022: "Environmental outcomes of the US Renewable Fuel Standard": "the carbon intensity of corn ethanol produced under the RFS is no less than gasoline and likely at least 24% higher"

Recent fraud concerns:

- Euractiv 2024: Discrepancy in British and Irish used cooking oil imports raises biofuel fraud concerns "A new analysis suggests more Malaysian used cooking oil was exported to Britain and Ireland than was collected in the country, raising fears that banned substances are being fraudulently passed off as the in-demand biofuel feedstock."

- BBC 2019: Used cooking oil imports may fuel deforestation

- Tagesschau 2025: Von falschen Klimazertifikaten und Palmölschwindel

9. Given recent biofuel fraud, how to you guarantee the sustainability of wastes and residues?

There have been several recent scandals with palm oil being incorrectly relabeled as used cooking oil, as well as fraud in the German GHG certificate scheme (see above), among many other cases of fraud.

The scientific view on lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions can also change over time as new data and methods become available.

One way to enhance the credibility of sustainability assessments would be to establish an independent scientific committee to regularly review the emissions factors assigned to different feedstocks.

Another way to raise credibility would be to only allow local wastes and residues to be used, i.e. avoid reliance on imported fuels, so that confidence in regulation is raised.

10. Is (e-)biomethane not a better solution than (e-)biomethanol?

Producing methane instead of methanol would allow more of current fossil gas demand to be directly replaced, and would reuse more of the existing methane infrastructure (pipelines, storage, end-use devices).

We would argue that:

- Future methanol demand is much more robust than methane demand in climate neutral scenarios.

- Many sources of biomethane, such as biogas plants, are not close enough to the current methane pipeline network to connect in a cost-effective way.

- As methane demand reduces, it becomes harder to maintain the methane infrastructure.

- Methane is a greenhouse gas with around 28 times the global warming potential over 100 years (GWP100) of CO2. Any leakage would contribute towards global warming.

Demand: The current methane demand mostly disppears in climate-neutral scenarios. Gas boilers for building heating are replaced by heat pumps; electricity generation from gas shrinks substantially; gas for non-energy use is replaced by hydrogen; gas for process heat is replaced by electrification, hydrogen and its derivatives.

Methanol is required, since it needed for high value chemicals (HVC), as a shipping fuel, and can also be used to make kerosene. These use cases make up 300-600 TWh/a each for Europe.

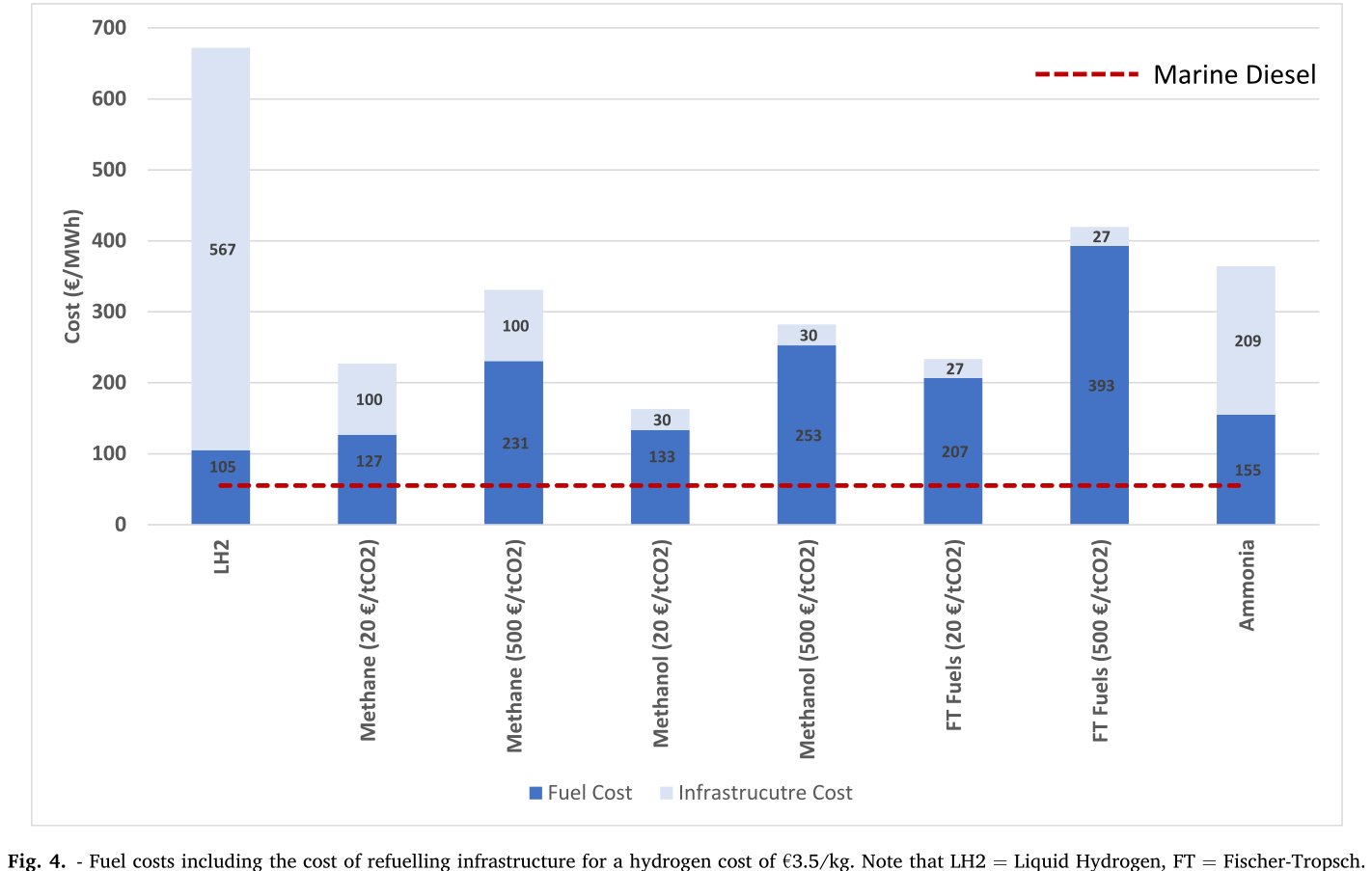

E-biomethanol would likely be cheaper to use in shipping than e-biomethane, as shown in the paper An assessment of decarbonisation pathways for intercontinental deep-sea shipping using power-to-X fuels (2024).

Figure 6: Costs for green shipping fuels (source: Gray et al, 2024)

The logistic costs of liquefied methane (LCH4) are simply higher than methanol, which is already liquid.

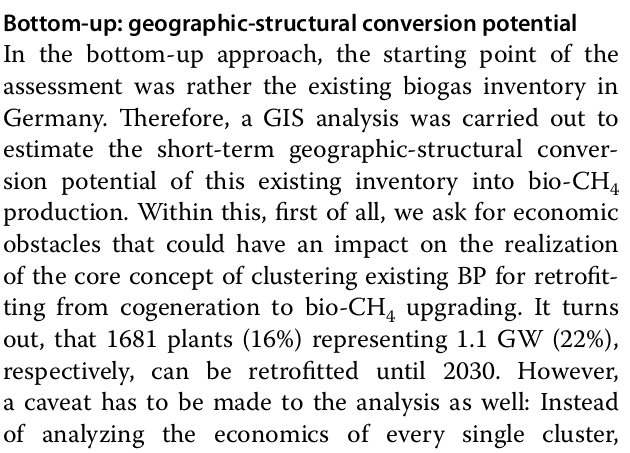

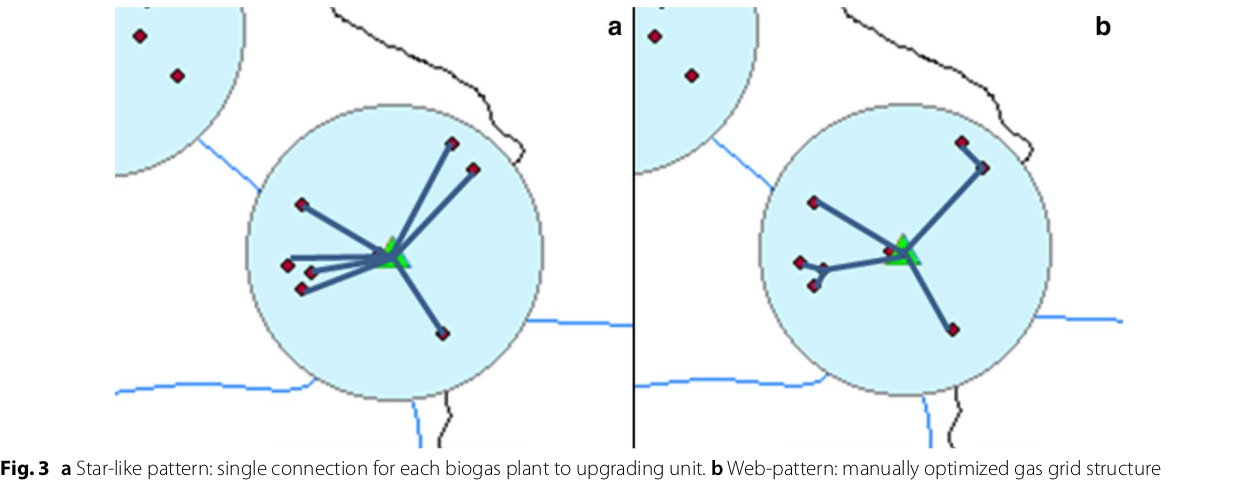

Pipeline proximity: As discussed in the blogpost What flexibility do we need from biogas?, in Matschoss et al, 2020 IZES and UFZ authors found that only 22% of today's biogas plants in Germany by kW output would be eligible for upgrading, even before further economic analysis.

Why are biogas plants so far from the gas grid? Biogas plants are deliberately located in rural areas near agriculture, whereas the gas network is optimised to bring gas to dense demand in industry and urban areas.

Figure 7: 22% biogas statistics (Source: Matschoss et al, 2020)

Uncertainty around future methane infrastructure: As building heating and other demands reduce, much of the distribution network for methane could be retired. This makes it still harder to connect biomethane producers.

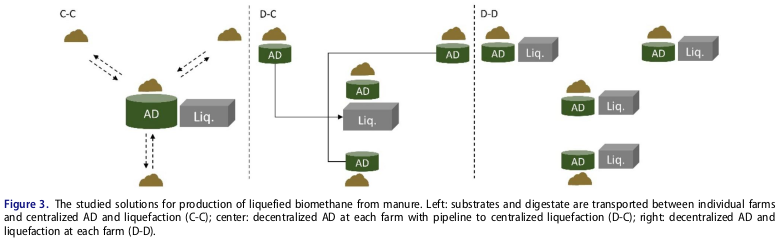

11. Can't e-biomethane be liquefied to gain similar advantages to e-biomethanol?

Some biomethane is liquefied already today for use by trucks. LCH4 could also be produced decentrally and brought to larger gas pipelines, to mitigate some of the issues of missing gas distribution.

For an idea what this might look like, see the Swedish paper Gustafsson, 2024 (Sweden has a limited gas grid; upgrading can be done cryogenically to match LCH4 temp).

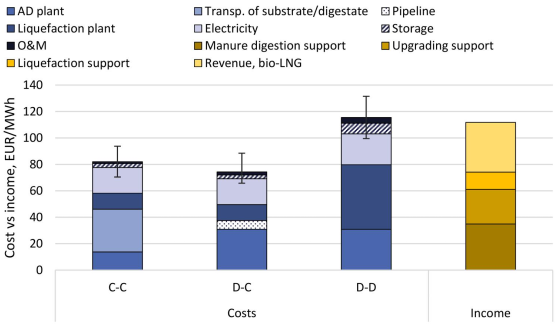

Figure 8: Swedish example: decentral/central setup for bio-LCH4 production. (Source: Gustafsson, 2024)

Figure 9: Swedish example: cost implications for bio-LCH4 production. (Source: Gustafsson, 2024)

However, we reiterate the point that future methane demand is expected to be small in climate neutral scenarios. Trucking is electrified, and for shipping methanol is a superior fuel to LCH4.

12. Aren't the costs of keeping the existing methane transmission network small?

The costs of maintaining the existing high pressure transmission network are very low when distributed over today's high consumption. However, with the lower methane demand of a climate neutral scenario, the specific costs per transported MWh would rise.

In addition, the distribution network costs to bring (e-)biomethane to it, and from it to the small number of users, could be quite high.

13. How would end-consumer prices of green methanol differ from hydrogen or methane?

In general the production costs of e-biomethanol are expected to be somewhat higher at ~180 EUR2020/MWh compared to ~100-120 EUR2020/MWh for e-hydrogen and ~120-150 EUR2020/MWh for e-biomethane beyond the year 2030. However, the costs of transporting and storing the hydrogen and methane are expected to be much higher than for methanol.

For example, consider the usage case of a hydrogen power plant running 500 hours per year paying a 25 EUR/kW/a network fee for peak demand (suggested by the German Federal Network Agency for the ramp-up of the German core hydrogen network). This translates to 25000 EUR/MW/a / 500 h/a = 50 EUR/MWh, which already closes the gap with methanol. Add in the costs for storing the hydrogen, and the cost advantage disappears.

Industry demand with constant hydrogen usage would pay a much lower network fee per MWh, and would see lower costs for hydrogen.

14. Wouldn't the large-scale use of methanol require methanol pipelines?

Methanol can be transported flexibly by truck, barge, ship, train or pipeline.

For large volumes pipelines are most efficient. Liquid fuels like crude oil and well as refined products like diesel, gasoline and kerosene are transported by pipeline today.

Methanol could reuse some of this pipeline infrastructure.

Liquid product transport by pipeline is considered to be easier to build, since the pipelines have a smaller diameter and don't offer the same dangers of explosion as hydrogen or asphixiation in the case of carbon dioxide.

15. Are CO2 pipelines required in the scenarios?

In the default scenarios we assume the availability of a CO2 pipeline to transport process emissions from industrial sites and biogenic CO2 to sequestration sites offshore as well as for fuel synthesis.

CO2 is transported by pipeline in a supercritical state cooled and under pressure as a liquid, so that the pipelines can have a narrow diameter. If the pipelines are not well regulated, accidents can be a threat to health (a pipeline accident in 2020 in Mississippi sent 45 to hospital, although this may have been due to hydrogen sulfide mixed in).

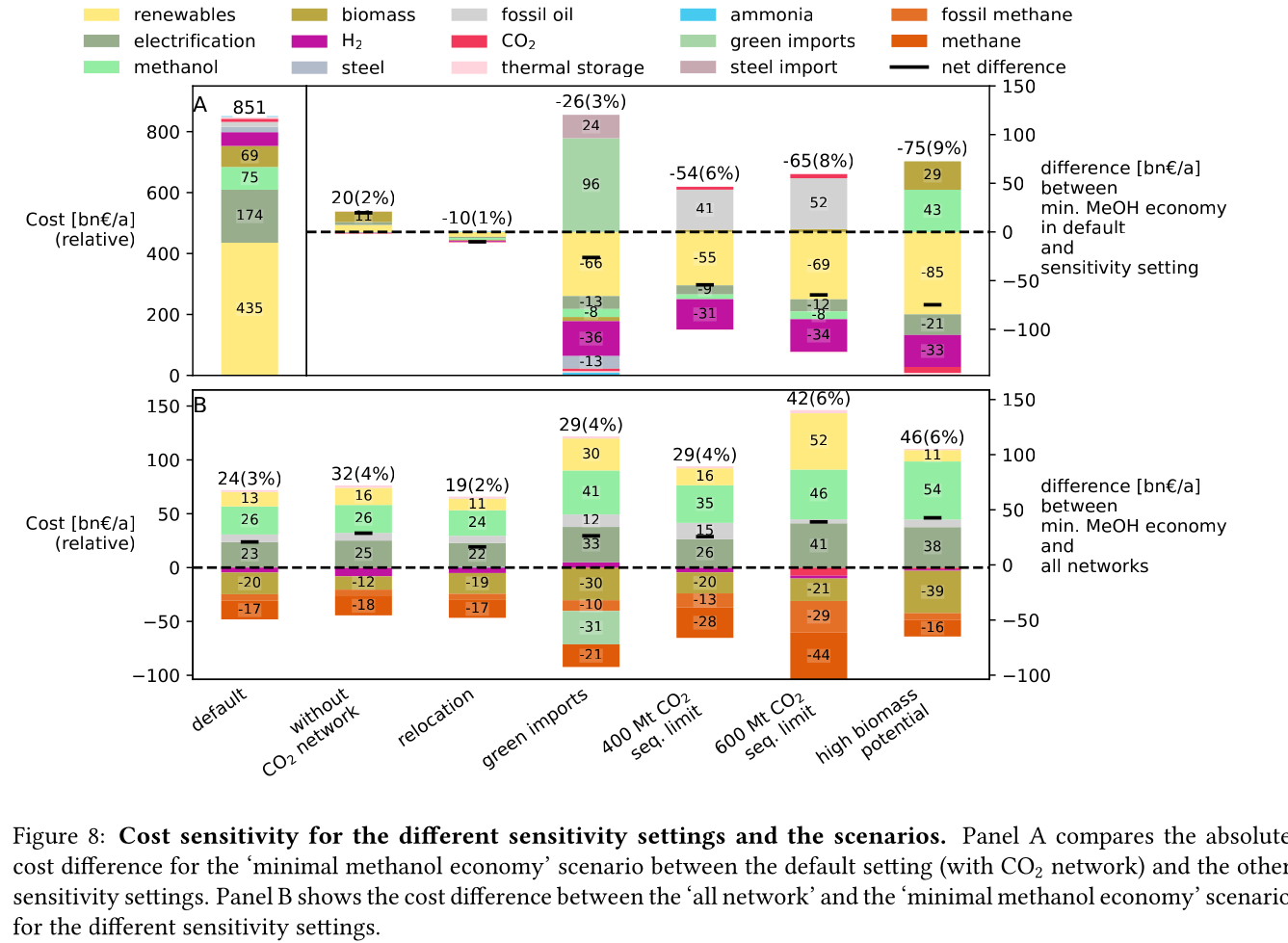

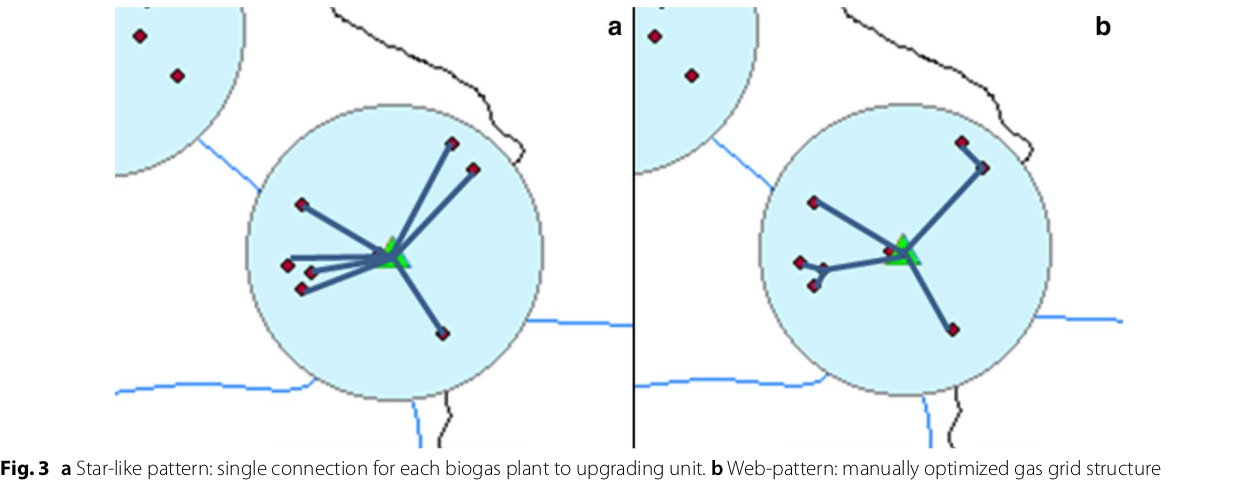

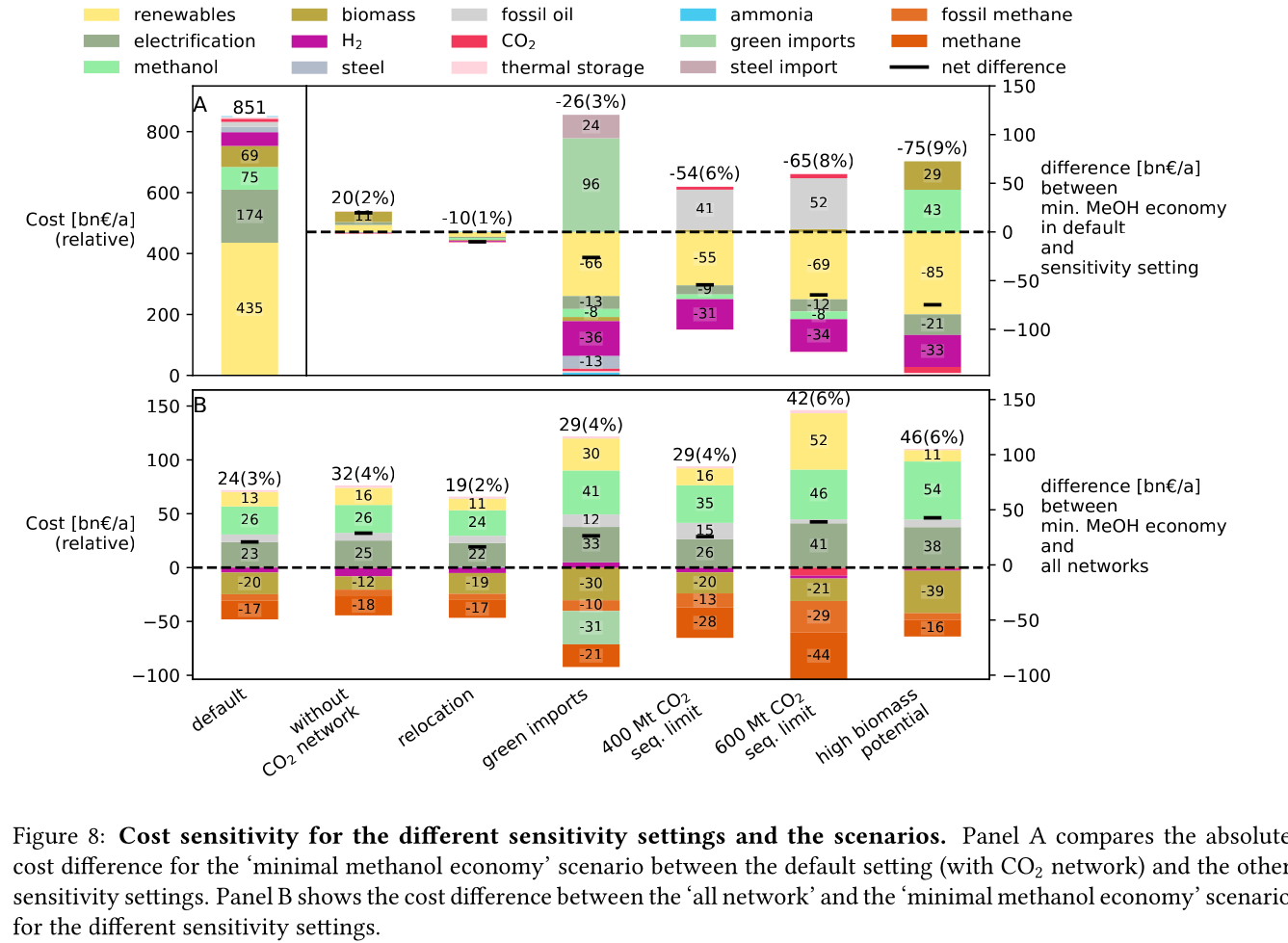

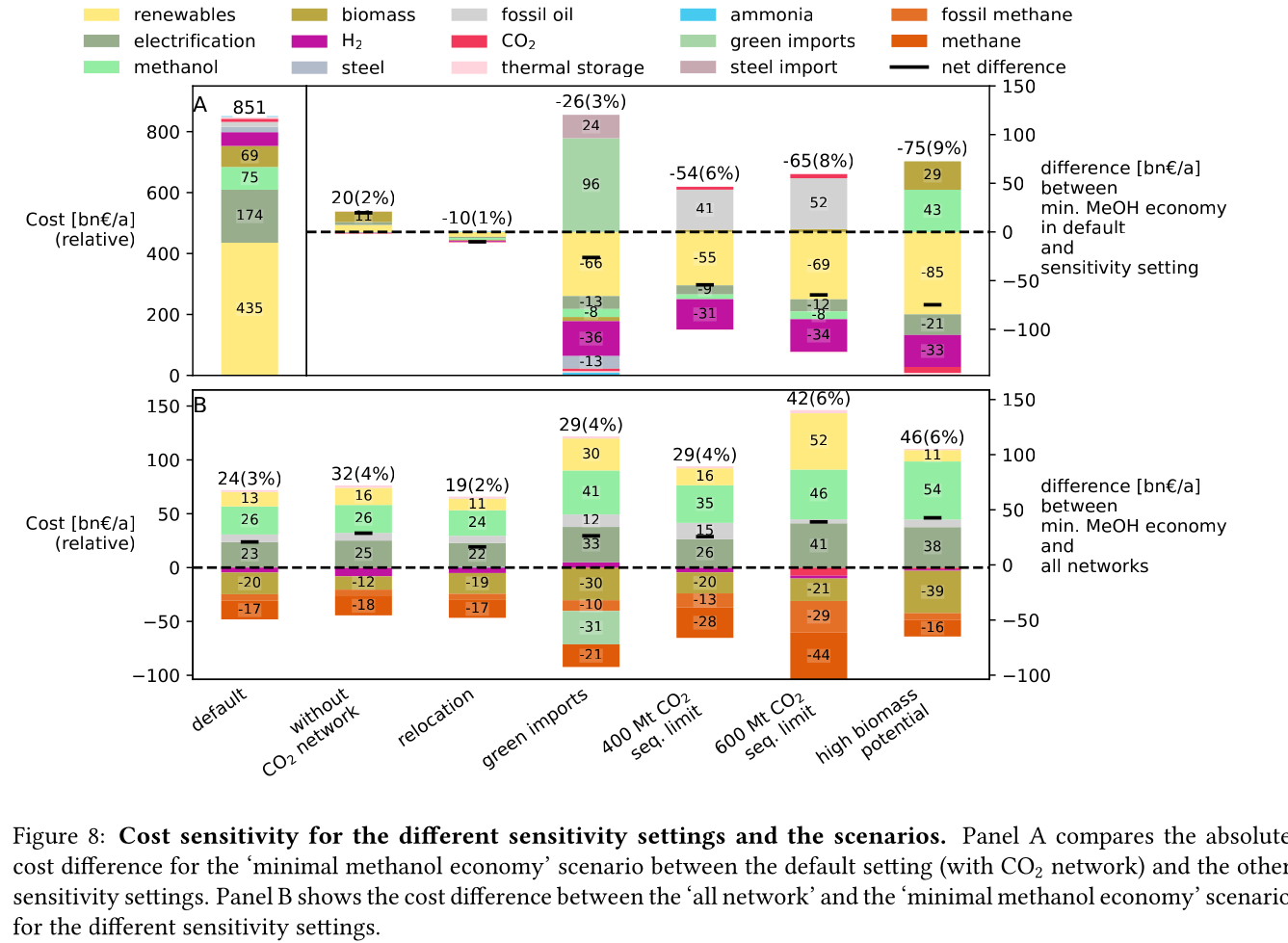

In a sensitivity calculation the removal of the CO2 pipeline raised costs by just 2% (forcing more biomass to be used for CDR to compensate industry process emissions that cannot be transported to sequestration sites):

Figure 10: Minimal methanol economy sensitivities

See also Hofmann et al, 2025 on the cost benefits of CO2 pipeline networks.

16. Are the logistic costs of transporting biomass and biogas included in the model?

Yes, solid biomass transport by truck is costed at 0.1 EUR/MWh/km (based on JRC-EU-TIMES). For biogas distribution via pipelines, costs are around 7 EUR/MWh for a 10 km distance (based on Gustafsson, 2024).

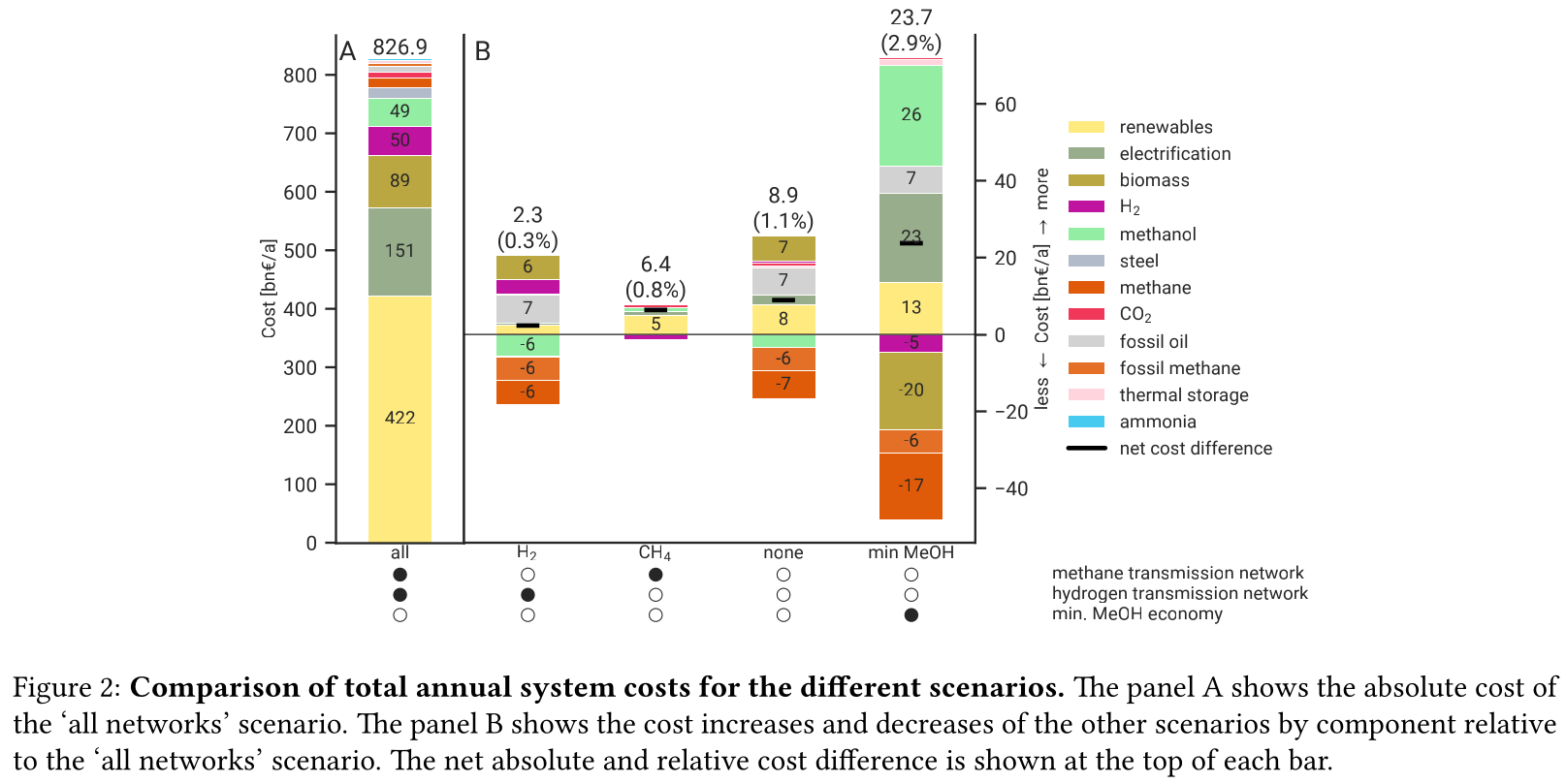

17. Why is the minimal methanol scenario more expensive?

The minimal methanol scenario was around 24 billion euros per year (3%) more expensive than the cost-optimal scenario.

The main cost drivers are:

- Methanol (~180 €/MWh) itself is more expensive than fossil gas compensated by carbon dioxide removal (~30 €/MWh + ~40 €/MWh) or electrolytic hydrogen (~100 €/MWh) because of the further conversion steps. Therefore whereever methanol is substituting methane or hydrogen, it is increasing costs. An extra cost of 100 €/MWh on 250 TWh/a for backup power and heat makes 25 billion euros per year.

- Decentral biomass boilers, allowed in the other scenarios, must be replaced by heat pumps in the "minimal methanol" scenario.

18. Are there resilience benefits to using methanol (e.g. dealing with shocks better, losses of pipelines)?

Yes, methanol tanks next to power stations is resilient against attacks on infrastructure.

Black-start-capable power plants follow this strategy: fuel oil bunkered next to diesel generators to restart the grid after a black out.

A similar strategy is followed in regions with unreliable power supply, where diesel generators are used for backup power supplies.

19. Is the Allam cycle generator required in order to close the carbon cycle for the scenario?

The Allam cycle generator uses pure oxygen to combust the fuel, allowing a pure stream of carbon dioxide to be captured from the exhaust. This reduces the energy requirements and costs for carbon capture. The use of the Allam cycle was explored in a previous paper with a toy model of the power sector.

However, once the concept is expanded to the full energy system like in the current paper, biogenic sources can be used for the methanol and the need to cycle carbon dioxide by capturing it is much reduced.

The model only builts 20 GW of Allam cycle running with full load hours of 1350. Costs would barely increase if the Allam cycle was disallowed and the model was forced to use CCGT instead.

The reason: the low running hours of the backup power plants tend to lead to low-capex solutions. Carbon capture is relatively high-capex.

The Allam cycle has seen recent delays and cost escalations in deployment, so it may be best to plan without it.

20. How easy is it to retrofit an existing gas turbine to use methanol?

Retrofitting gas turbines from methane to use methanol is relatively simple and substantially easier than retrofitting for hotter-burning hydrogen. Burners and fuel delivery must be changed, and mass flow adjusted. Since methanol burns at a lower temperature than methane, it reduces the formation of unwanted NOx emissions.

For a large gas turbine the cost of conversion from oil to methanol was estimated to be 3 million USD (i.e. 6 USD/kW for a 500 MW plant) (Bertau et al, 2014).

A gas turbine in Israel was already converted to methanol to meet strict NOx and other emission standards.

The Siemens gas turbine SGT-400 is sold as running on methanol.

See also the Methanol Institute's power generation page.

21. What is the typical size envisaged for a methanol synthesis plant? How many would be needed in Europe/Germany?

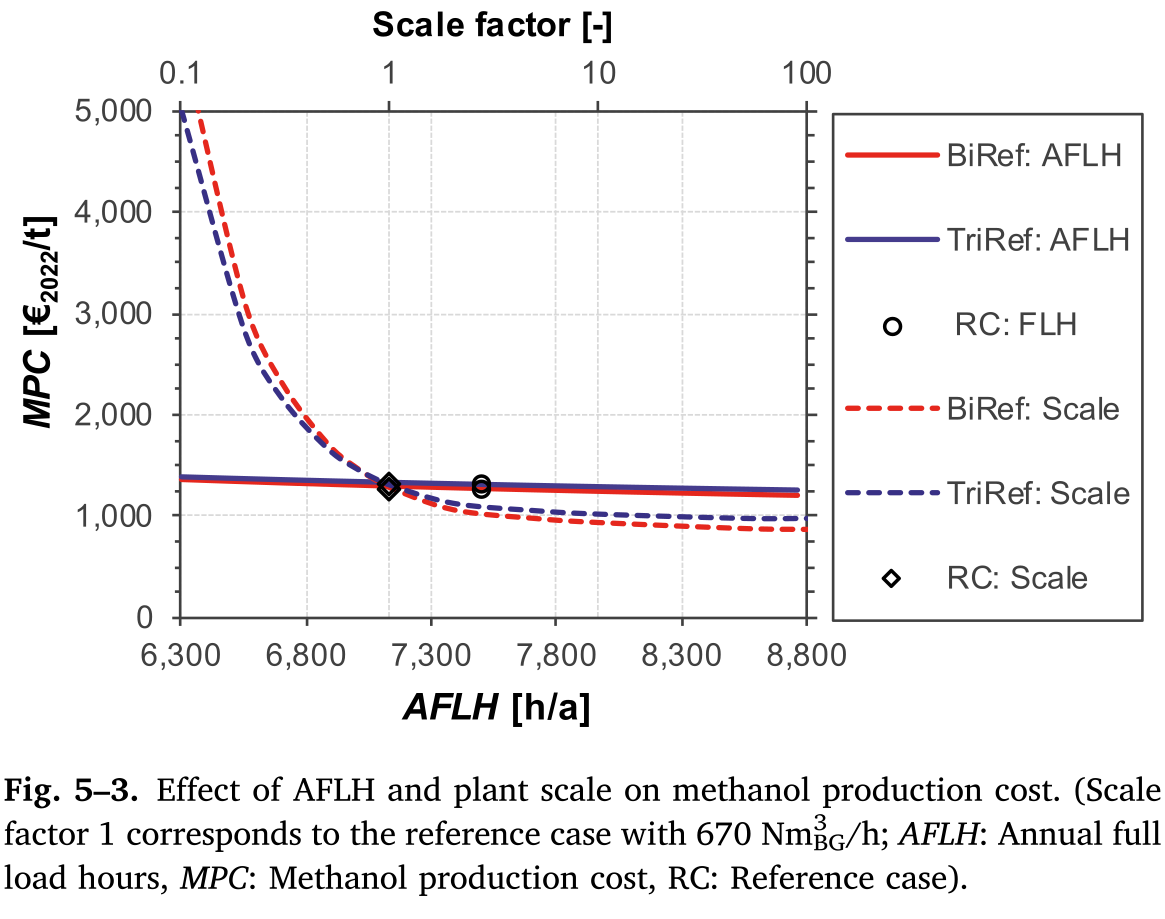

Both methanol synthesis and gasification need to take place at double-digit-MW scale to benefit from lower specific costs. Unlike other components that are linear beyond MW-scale (electrolysis, PV, batteries, biogas plants, biogas upgrading), they benefit from these large economies of scale.

Literature indicates that the production size should be at least 25 MWMeOH or around 35 ktMeOH/a when operating for 8000 hours per year.

Ideally for lower costs it should be more like 100-200 ktMeOH/a, i.e. 75-150 MWMeOH.

Figure 11: Production cost of methanol from biogas in dependence of scale (upper axis); factor 1 is around 6 ktMeOH/a; 800 EUR/tMeOH is 144 EUR/MWhMeOH,LHV (source: Bube et al, 2024)

For Europe's 1500 TWhMeOH/a demand, this would be around 2300 plants of capacity 75 MWMeOH, or 1150 plants of size 150 MWMeOH. (Comparison: there are more than 10,000 biogas plants, over 200 biorefineries for biofuels and 90 oil refineries in Europe.)

For German needs of 200 TWhMeOH/a this would be around 330 plants of capacity 75 MWMeOH. (Comparison: there are around 10,000 biogas plants in Germany today.)

Assuming residues were collected from 170,000 km2 of agricultural land in Germany, each plant would have a catchment area of around 500 km2, i.e. a radius of around 13 km. Whether biomass is transported to a central processing plant, or processed to biogas or biocrude decentrally before transport, is open to optimisation.

Example of small biogas networks aggregating:

Figure 12: Local biogas pipeline networks aggregate small biogas units for conversion (Source: Matschoss et al, 2020)

Depending on the mixture of available substrates, either biogas or gasification units or both could serve each methanol synthesis unit.

Gasification plants benefit from the same economies of scale as the methanol synthesis. For the cost assumptions the model uses from the Danish Energy Agency's Renewable Fuels Technology Catalogue it is assumed than the gasification to methanol plant has a scale of 200 ktMeOH/a by 2030.

22. How would methanol be transported away from each methanol plant?

200 ktMeOH/a production capacity corresponds to 550 tMeOH/d, which could be transported away by 22 truck trips per day carrying 25 tMeOH each.

Multiple methanol plants could be aggregated to a multi-MtMeOH/a pipeline.

There are many pipelines today for crude oil as well as refined products like gasoline, diesel and kerosene.

23. How would existing biogas units fit into the minimal methanol economy?

As discussed above, most biogas units today use unsustainable feedstocks like maize. If the substrates can be exchanged for biogenic residues (e.g. manure, straw) and wastes, the existing biogas units could play an important role.

Many existing biogas plants are smaller than the scale needed for methanol synthesis. However, several small plants could be linked up together in a local biogas pipeline network to feed a single synthesis unit. There are examples of small biogas pipeline networks in Germany today.

Figure 13: Local biogas pipeline networks aggregate small biogas units for conversion (Source: Matschoss et al, 2020)

24. How would existing bioethanol and biodiesel plants fit into the minimal methanol economy?

As discussed above, most 1st generation biofuels are not sustainable from a life cycle perspective. Bioethanol often uses maize, while biodiesel often uses oils from rapeseed, palm or soy. There are unlikely to be enough sustainable sugary feedstocks for bioethanol or oily feedstocks for biodiesel to be able to reuse many of the existing facilities.

The know-how at the facilities could however be integrated into methanol synthesis plants.

25. How would the results change if a lot of carbon sequestration or cheap carbon dioxide removal were available?

The default scenarios in the paper allowed 200 MtCO2/a sequestration in offshore saline aquifers and depleted oil and gas fields. This is enough to sequester all industry process emissions as well as some carbon dioxide removal (CDR).

Comparable studies have similar assumptions. The CCS-friendly CATF included at most around 300 MtCO2/a in their scenario for Europe for 2050. The EU Commission's Carbon Management Strategy has around 250 MtCO2/a in 2050.

To explore the dependence on sequestration volume, we varied it in two sensitivities with 400 and 600 MtCO2/a. Since using fossil fuels and compensating with CDR from bioenergy with CCS (BECCS) is generally cheaper than CCU, the scenarios are lower cost.

Figure 14: Minimal methanol economy sensitivities

At 400 MtCO2/a the use of methanol for HVC (MtA/O) and kerosene is reduced; methanolisation reduces to compensate:

Figure 15: Energy balances for sensitivity with 400 MtCO2/a sequestration.

At 600 MtCO2/a the main use is in shipping; methanol is still made from biogas with a little extra from solid biomass:

Figure 16: Energy balances for sensitivity with 600 MtCO2/a sequestration.

26. Isn't it always cheaper to sequester a tonne of carbon dioxide than to use it in a fuel?

In principle it is cheaper to sequester a tonne of biogenic CO2 to compensate for a tonne of fossil fuel use than to use it in a synthetic fuel. If the transport and sequestration costs 100 EUR/tCO2, the abatement cost could be around 150 EUR/tCO2, while for the synthetic fuel it could be 300-400 EUR/tCO2.

However, as discussed above, the sequestration volume per year is expected to be much lower (200-300 MtCO2/a) than that need to compensate all shipping and aviation emissions with CDR (500-700 MtCO2/a). This is because of the need to expand the rate (in MtCO2/a) in time for 2050, rather than a limit on the total of CO2 that can be stored offshore (which could be as high as 100 GtCO2).

Furthermore, upstream emissions from fossil fuel usage must also be compensated, along with the higher contrail formation with fossil fuels.

Furthermore, transporting CO2 from many decentral biomass sources would require pipelines and trucks. CO2 transport is likely to have lower acceptance than methanol, since CO2 is an asphyxiating gas.

27. What is the carbon dioxide abatement cost of e-biomethanol?

The carbon dioxide abatement cost, measured as the shadow price of the constraint limiting carbon dioxide emissions to net-zero, varies depending on the scenario. If we stick with the methanol economy and keep the sequestration limit tight (200 MtCO2/a), it's 426 €/tCO2, if we relax to 400 MtCO2/a it drops to 335 €/tCO2, then at 600 MtCO2/a it's just 124 €/tCO2. As sequestration is relaxed, CCU is replaced by fossil+CDR. That last value is quite low because the model is forbidden in that scenario from using fossil gas as a gas. If fossil gas allowed with 600 MtCO2/a sequestration, the price rises to 239 €/tCO2, since that's cheaper than making fossil methanol.

While these abatement costs are high, there are two important points to bear in mind:

- The climate damage from emitting a tonne of CO2 are this high. The German Environmental Agency estimates the climate damage of a tonne emitted in 2050 at 435 €2024/tCO2 (assuming a 1% time preference rate).

- The high abatement costs are marginal costs for the last few 100 MtCO2/a of abatement in Europe. Most of the greenhouse gas reduction happens at a much lower marginal cost. For example, if the last 300 MtCO2/a of reduction has a marginal abatement cost of 200 €/tCO2 higher than the rest, this means extra costs of 300*200 mn€/a i.e. 60 bn€/a or around 130 € per citizen.

See BlueSky discussion.

28. What path dependencies are locked in by pursuing e-biomethanol?

Very few. Methanol synthesis plants can be flexibly repurposed for e-biomethane or for biomethane/ol or to export excess CO2 for sequestration (i.e. carbon dioxide removal).

29. Path to climate neutrality: could you start producing (e-)biomethane, then switch to (e-)biomethanol later?

Some infrastructures would be in common: collection logistics for biomass, use of syngas for methane/methanol synthesis.

30. Do any e-biomethanol plants exist today?

The Kasso e-methanol plant (42 kt/a) in Denmark started operation in March 2025 and was the largest, using CO2 from a nearby biogas plant.

Since then in July 2025 a 50 kt/a plant went online in China using biomass gasification and electrolytic hydrogen, Shanghai Electric's Taonan plant, and several more in China are under construction.

Hanno Böck's Feb 2025 summary of active e-biomethanol projects

31. Who would the first users of green methanol be?

Shipping companies like Maersk are already signing offtake agreements for green methanol for their ships. Customers for the Kasso plant include Maersk, Novo Nordisk and Lego.

32. What provides industrial process heat in the model?

A large fraction of industrial process heat is electrified in the model, following the 2035 potentials in Agora's 2024 study on industrial process heat electrification. Existing biomass uses, such as in the pulp and paper industry, are left as they are. Methanol is used for the flat glass industry, although it is not as good at providing radiant heat as methane (ironically due to methane's unclean burning compared to methanol).

33. There is significant methanol usage even in the reference cost-optimal case - aren't all the scenarios methanol scenarios?

Yes, methanol usage for shipping, producing kerosene and high value chemicals (HVC) is prefered in the model over alternatives (other fuels for shipping (although model isn't offered full pallette), Fischer-Tropsch for kerosene and naphtha for HVC).

The main differences between the scenarios is the use of fuels for backup electricity and heat.

34. What if green methanol were imported?

In the paper the import of green methanol from outside of Europe was only allowed in the scnario "green imports" along with imports of green steel and green ammonia:

Figure 17: Minimal methanol economy sensitivities

This reduces the cost of the minimal methanol economy scenario by 26 bnEUR/a (3%), see Panel A.

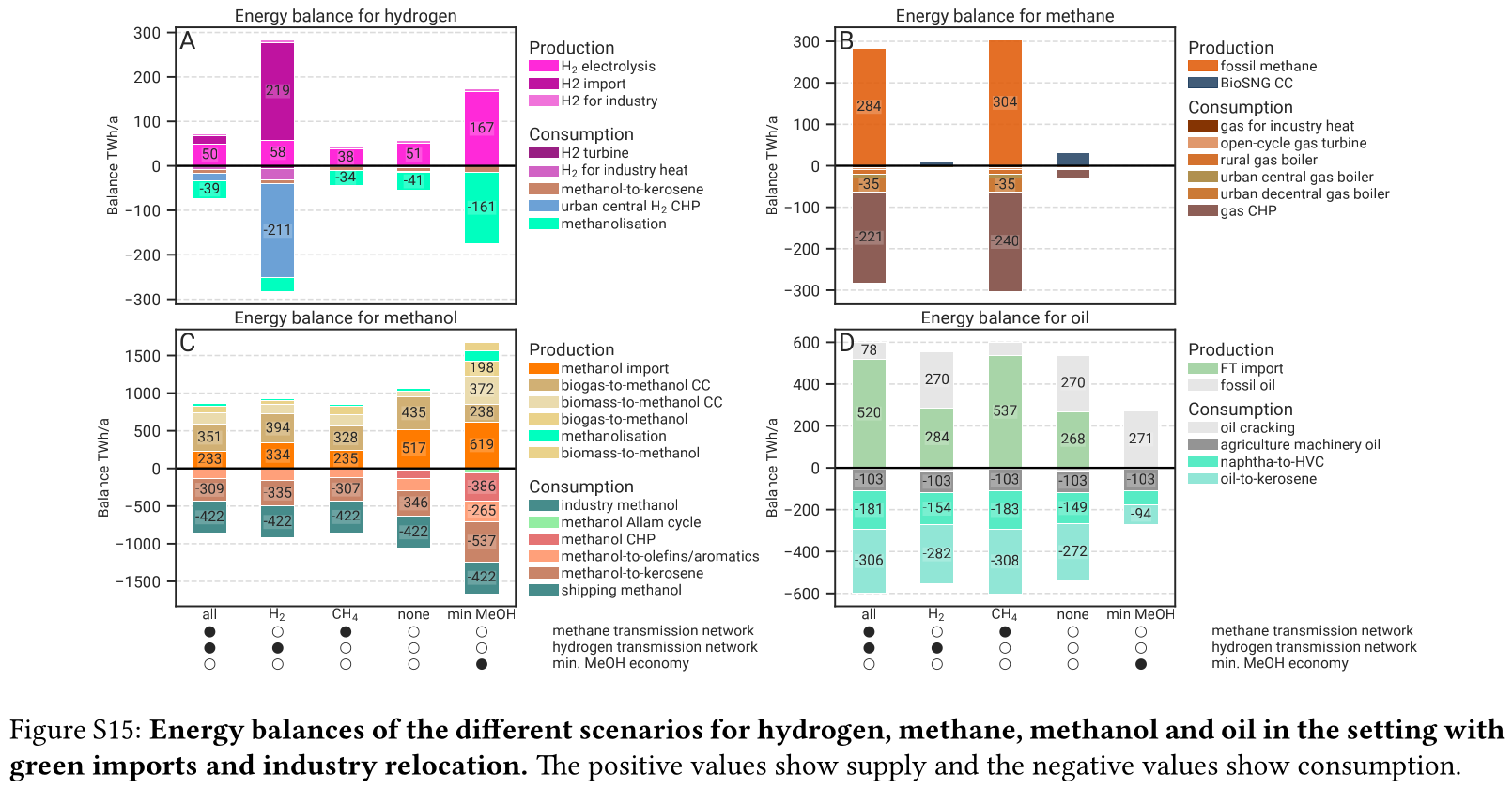

In the minimal methanol scenario, 619 TWh/a of 1550 TWh/a total methanol is imported:

Figure 18: Energy balances for sensitivity with green imports

Hydrogen production in Europe is much lower than in the default scenario.

Since the sustainability of carbon sources abroad cannot be guaranteed, it was assumed that direct air capture was used to source the carbon dioxide. This makes the methanol more expensive. Some sites in Europe can compete with these imports, because they have both biogenic carbon dioxide and cheap hydrogen.

There has been significant fraud with the sustainability criteria of imported biofuels (see discussion of biofuels above), so this would have to be carefully regulated.

Since biogenic wastes and residues are limited worldwide, it might make sense for Europe to cultivate its own biogenic biomass to maximise supply.

35. Which technology innovations would improve the case for a minimal methanol economy?

The following innovations would improve the case for a minimal methanol economy:

- Methanol catalysts that would allow more flexible operation, allowing the synthesis to shut down during periods of low wind and solar.

- Methanol catalysts that work at lower pressures and temperatures, allowing smaller less complicated synthesis units, like the novel homogeneous liquid catalyst from carbon.one.

- Plant breeding or genetic engineering to improve the fuel yield of the biomass substrates.

- Improvements and cost reductions to solid oxide electrolysers that allow heat integration with methanol synthesis, and possible reverse operation as fuel cells.

36. Which technology innovations would worsen the case for a minimal methanol economy?

The following innovations in competing technologies would worsen the case for a minimal methanol economy:

- Cheap and plentiful carbon dioxide removal options (e.g. burying biomass, innovations in carbon sequestration).

- Improvements to synthesis of competing liquid fuels, e.g. ethanol, DME or Fischer-Tropsch.

- Electrification concepts for long-haul aviation or shipping.

- Onboard carbon capture on ships (although this could work with the methanol economy).

- Increase in plastic landfilling, which would act like carbon sequestration and reduce the need for primary green HVC.

These technologies would allow methanol use to further be minimised. A "minimal methanol" economy can also be a "no methanol" economy.

The fact that methanol does not rely on complex interlinked infrastructure, allows methanol production targets to be easily adjusted downwards, unlike hydrogen, that needs complex coordination of pipelines and underground storage.

37. Is methane/hydrogen value chain leakage an argument for methanol?

Methane is a greenhouse gas with around 28 times the global warming potential over 100 years (GWP100) of CO2. Hydrogen is an indirect greenhouse gas (it prolongs the life of methane in the atmosphere) with a GWP100 of 11.6 ± 2.8 (Sand et al, 2023). Any leakage of methane or hydrogen could weaken the case for these energy carriers.

Methane leakage from extraction, transport and storage can be as high as 5% or more across the value chain (Weller et al, 2020). However, producers such as Norway have managed to regulate leakage successful to keep it below 1%.

Biogas production is one source of carbon in the minimal methanol concept, so would also have to be regulated carefully.

TODO: 2025 paper: Assessing hydrogen supply chains: An integrated review of leakage and energy efficiency studies: "gaseous H2 systems have ∼4.5% leakage"

38. Is there any similarity with cellular approaches for energy supply?

Compare: VDE: The Cellular Approach.

Some similarity, in that a 100-200 ktMeOH/a synthesis plant with a biomass collection area of 500-1000 km2 determines a cellular structure.

39. How flexibly must the electrolysis and methanol synthesis be operated?

See Taslimi & Khosravi, 2025 for Kasso plant: electrolyser operates 75-80% capacity factor; shutdowns can be minimised; hydrogen is buffered in storage; methanol synthesis runs with 90-95% capacity factor.

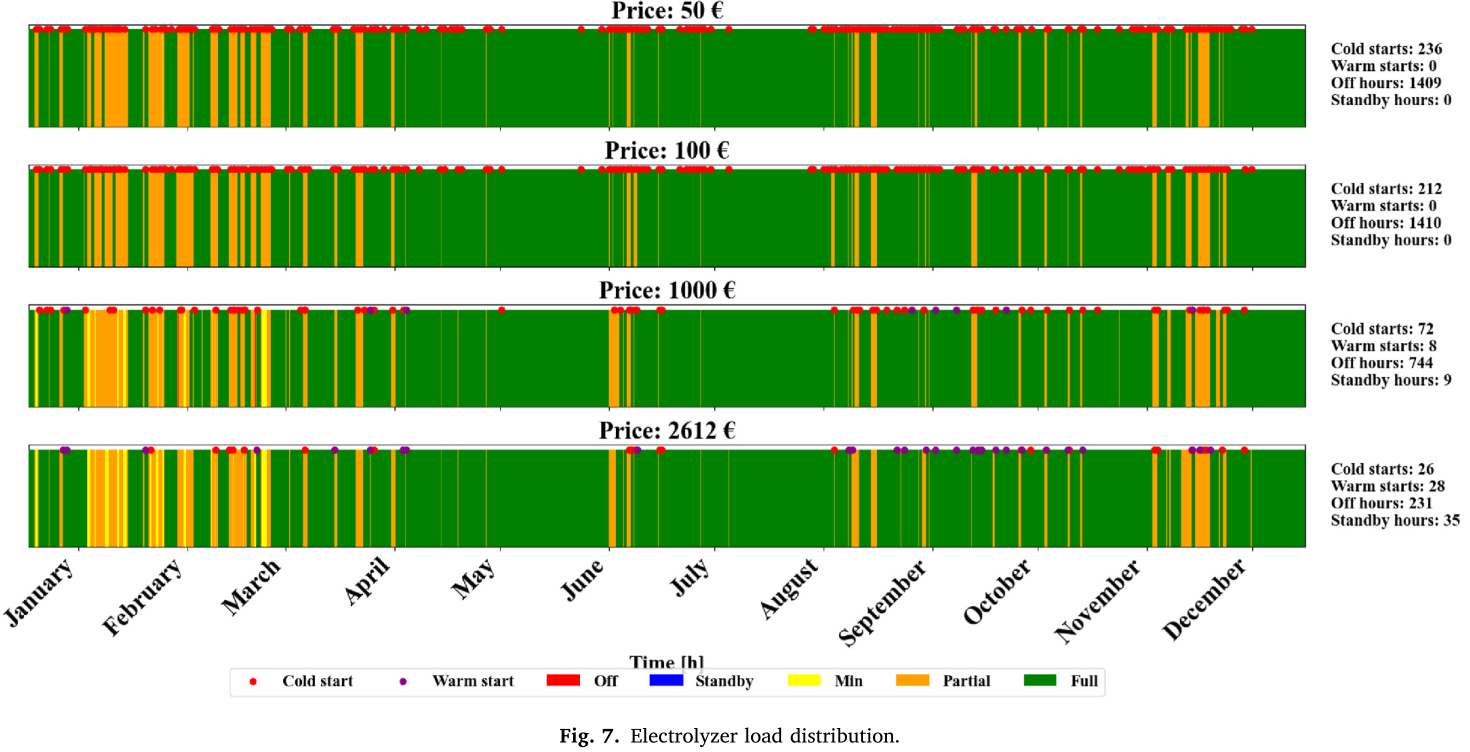

Figure 19: Examples of electrolyser operation from optimisation with different cost penalties for cold starts ranging from 50 EUR to 2612 EUR; high penalty means around 9x fewer cold starts (source: Taslimi & Khosravi, 2025)

40. How are agriculture and forestry affected by the "minimal methanol" concept?

The careful collection and processing of biomass wastes and residues, primarily from agriculture and forestry, put agriculture and forestry at the centre of the "minimal methanol" economy. Whether down a CCU or CDR route, sustainable biogenic CO2 takes centre stage.

Coordinating carbon management with food production, to avoid indirect land use from fuels, becomes very important.

Methanol production would provide a more stable, climate-friendly and higher income level than current biofuels or biogas production.

41. Could more CO2 be captured and cycled back to methanol production?

Let's run through the use cases of methanol that could incorporate CO2 capture:

- Aviation: Many technical challenges here; could power electric motors with fuel cells equipped with CO2 capture, but CO2 itself would be too heavy and bulky to transport.

- Shipping: Here there are several concepts to allow onboard capture and unload liquid CO2 at port.

- Waste-to-energy plants: WtE plants with carbon capture are already included in the model; they run baseload to process waste that cannot be landfilled.

- Peaking power plants: As discussed above in relation to the Allam cycle, carbon capture is CAPEX-intensive and doesn't match the economics of plants that run for just a few hundred hours a year (which are generally low-CAPEX, high-OPEX, see screening curve analysis).

42. Could CO2 be exported for methanol synthesis outside of Europe at sites with cheap green hydrogen?

Mitsui and Mitsubishi are working on a ship than would transport LCO2 to a methanol production site and transport methanol back.

The volumes of liquid would match well (1 MWh of methanol has a volume of 0.23 m3 and requires 0.248 tCO2 with a liquid volume of 0.23 m3), but the CO2 is 38% more massive. The CO2 also needs to be cooled and transported under pressure.

43. How are steel and ammonia produced in the model?

Steel and ammonia are produced using local hydrogen production in the "minimal methanol" scenario.

If existing sites in Europe for steel and ammonia are used, these are sub-optimal for hydrogen production, so the model transport some methanol to these sites for steam-reforming back into hydrogen.

If steel and ammonia can relocate within Europe (scenario "relocation") then they move to good H2 sites and the model avoids steam-reforming methanol:

Figure 20: Minimal methanol economy sensitivities

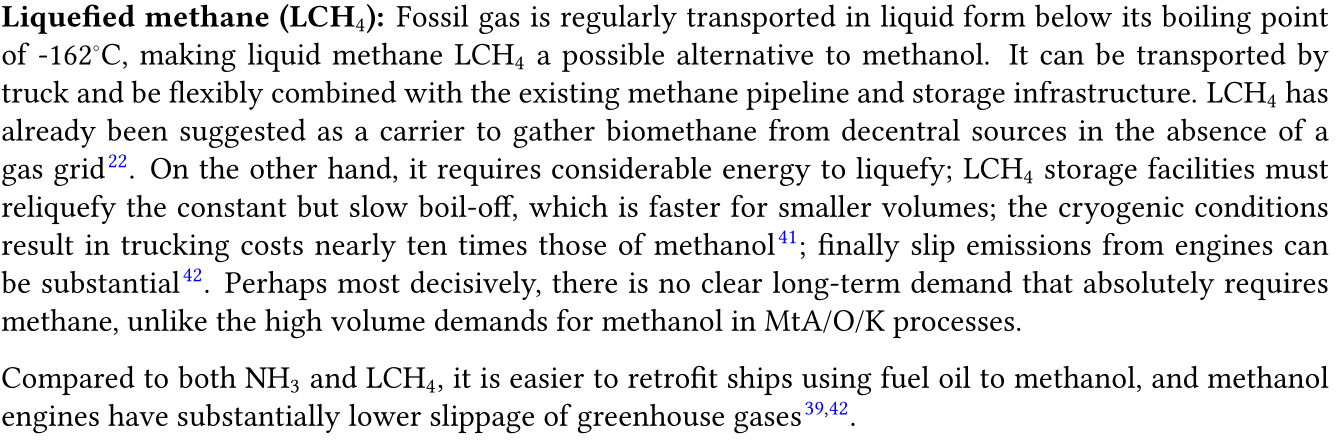

44. Aren't ammonia, LCH4, LH2, ethanol, LOHC, DME, or Fischer-Tropsch fuels better than methanol as an energy carrier?

Here are the relevant sections from our 2025 paper The Minimal Methanol Economy as a Gap-Filler for High Electrification Scenarios that discuss alternative energy carriers.