Solar and batteries can power the world

First Posted: 2026.02.09, Last Revised: 2026.02.19, Author: Tom Brown

Solar and batteries are cheap enough that most people can get most of their electricity from them, and save money. This equation gets better and better over time as their costs decline.

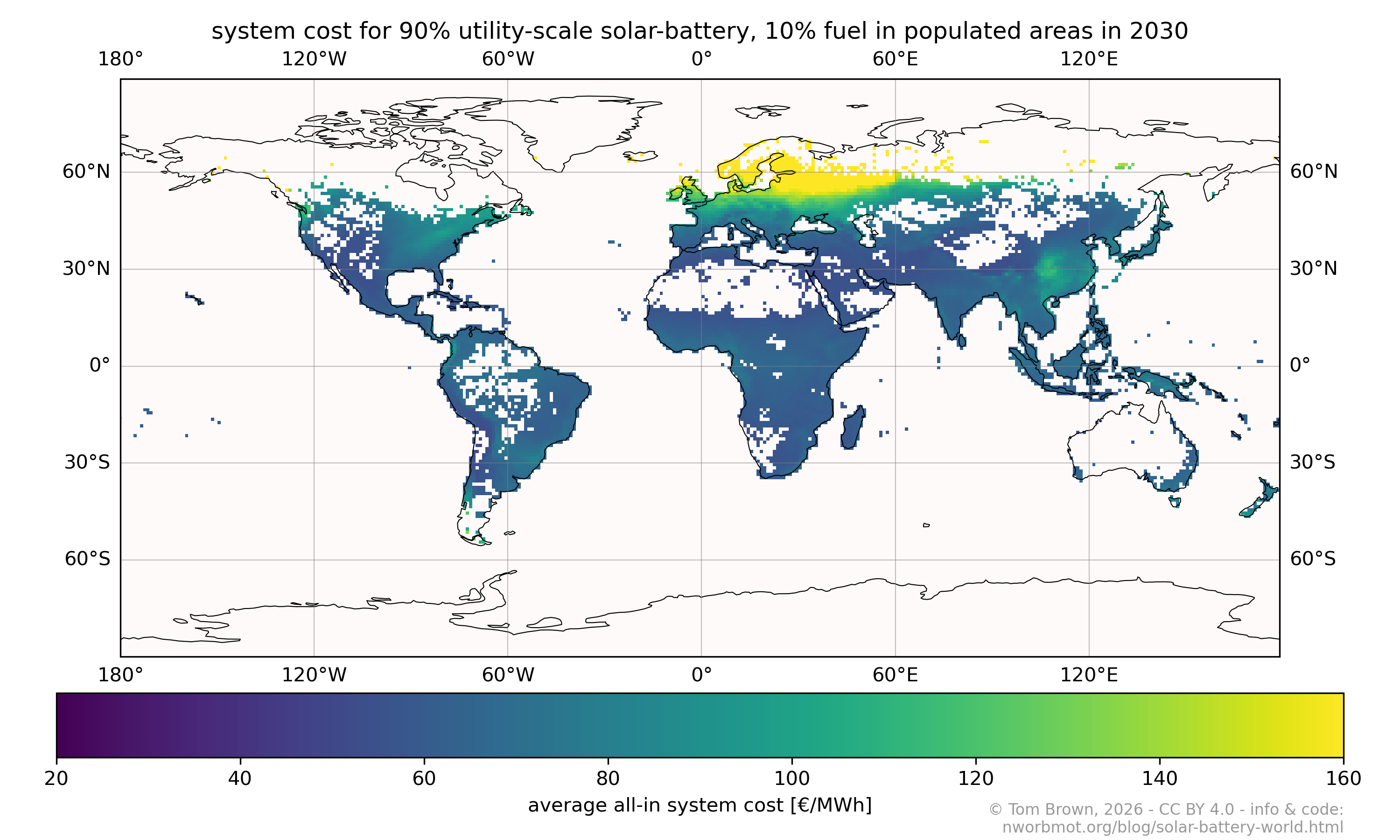

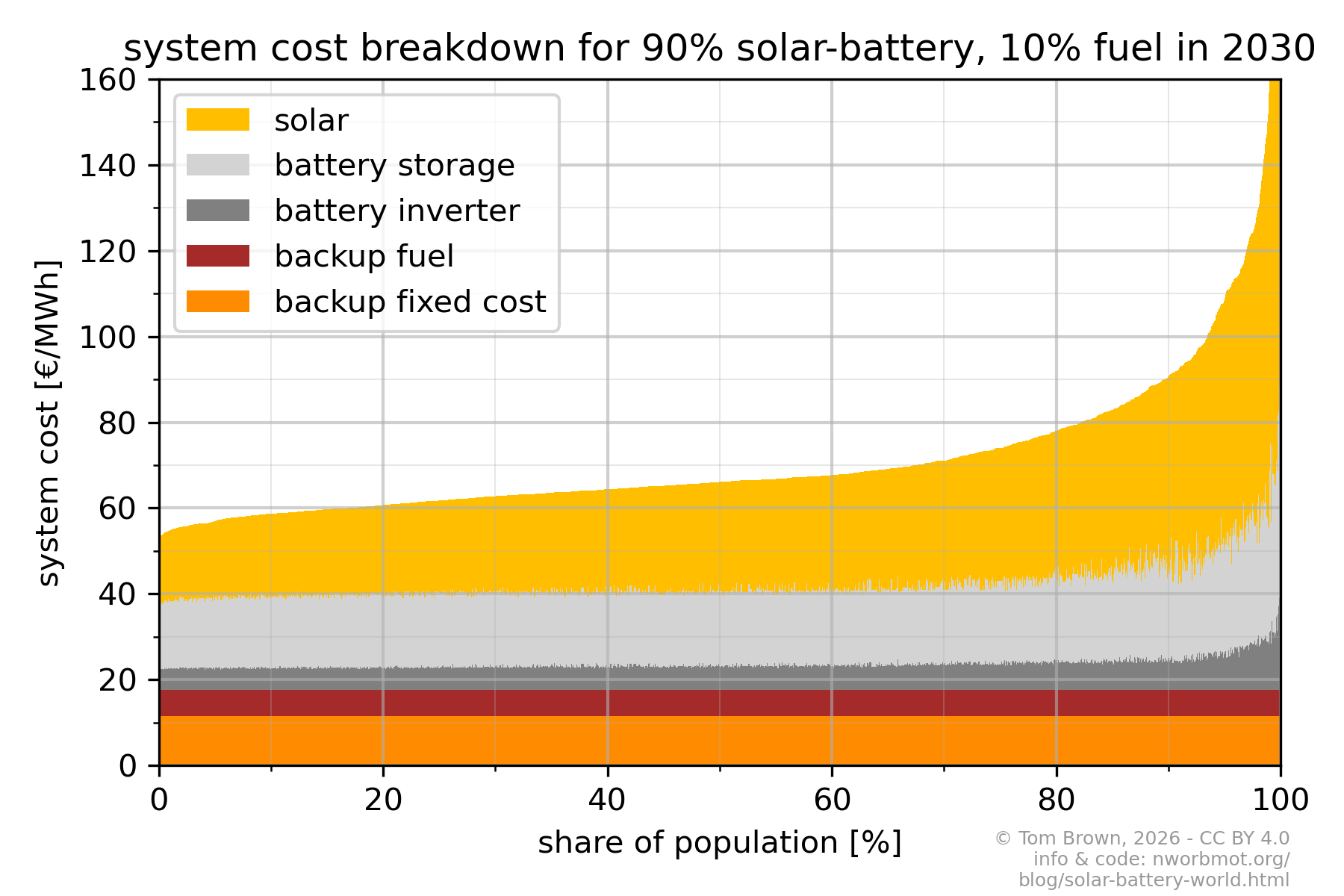

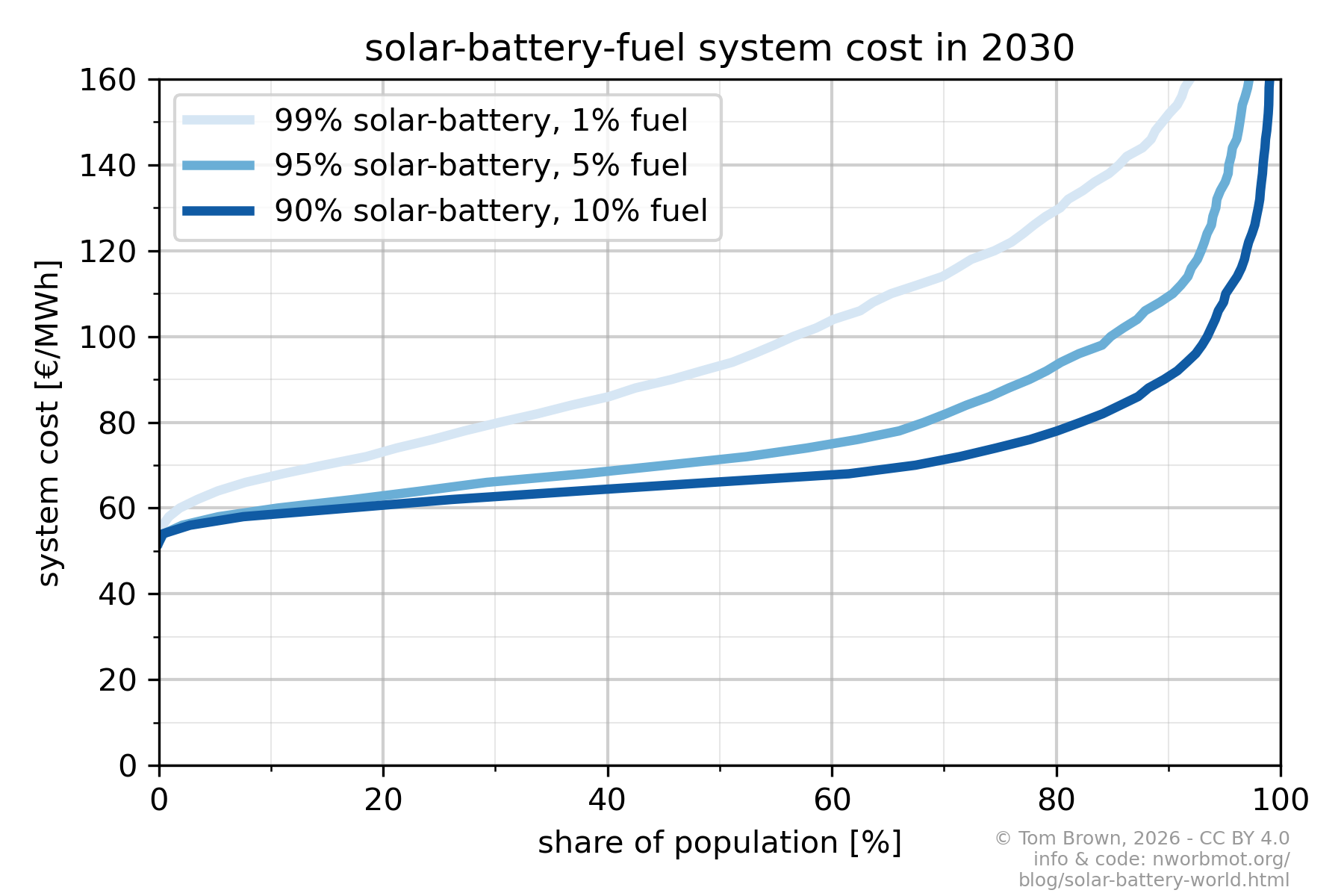

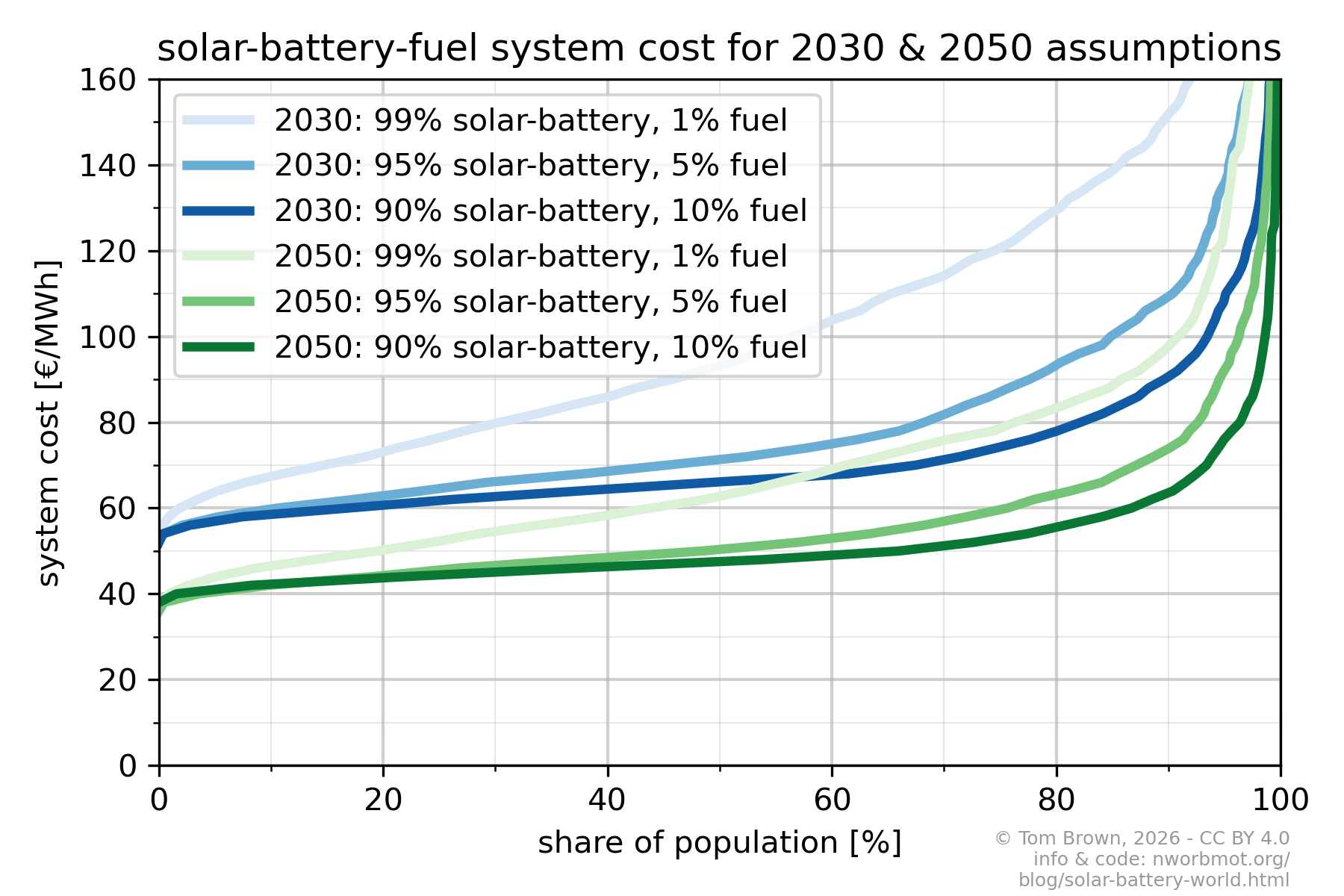

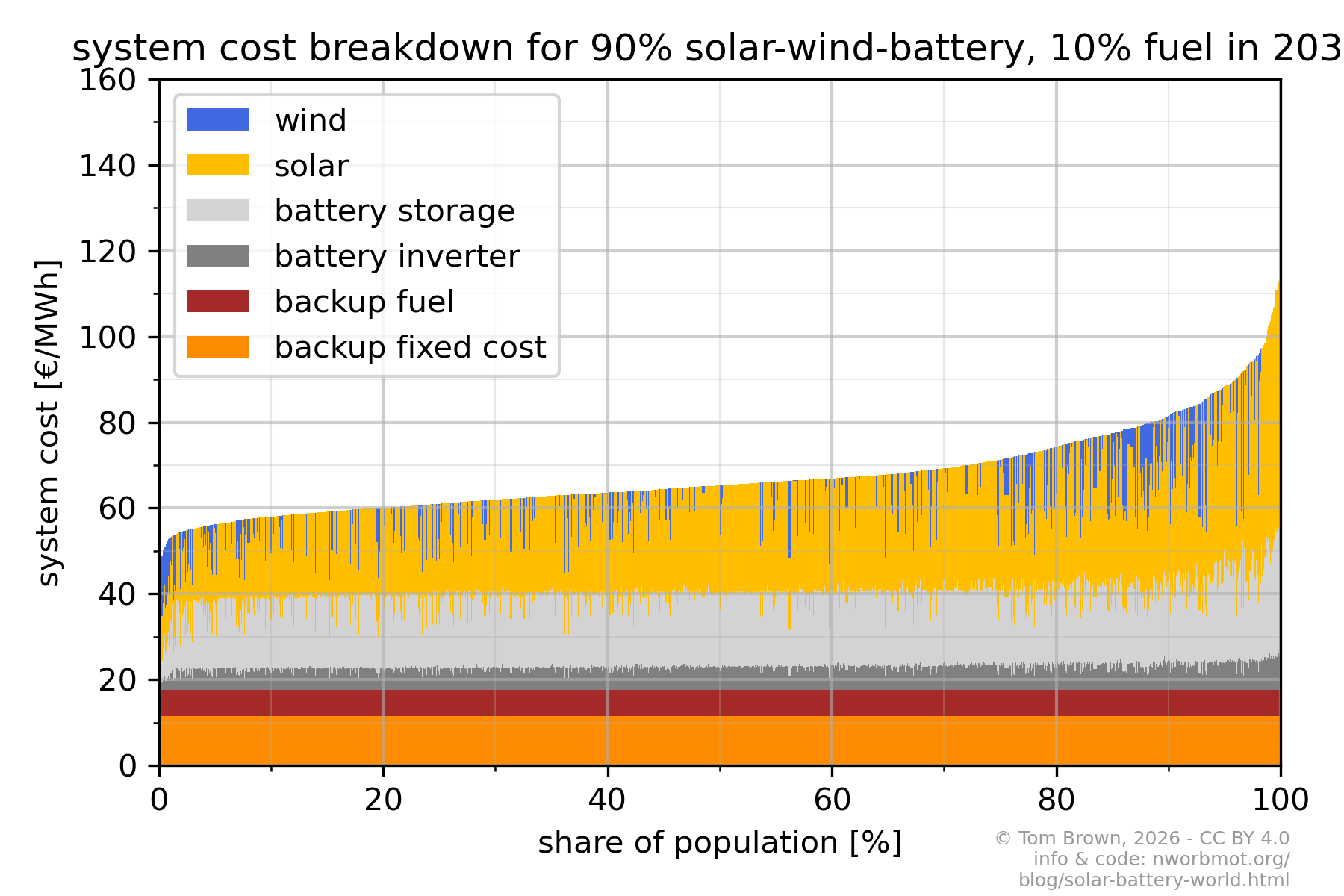

More precisely: solar and batteries can supply 90% of electricity for 80% of the world's population at less than 80 €/MWh (including a fuel backup) with 2030 assumptions. Add some wind, existing hydro, or wait a few more years for costs to decline, and the equation just gets better.

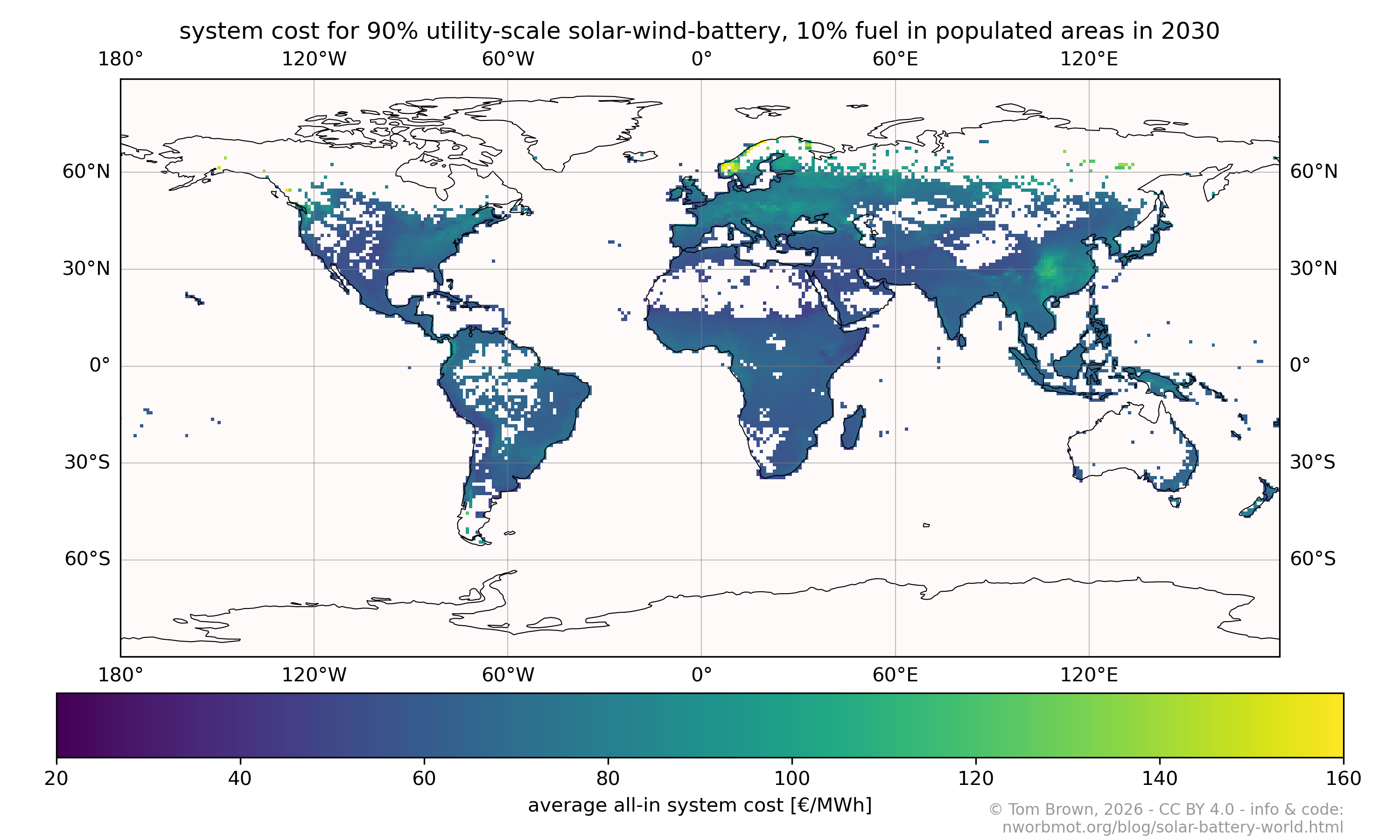

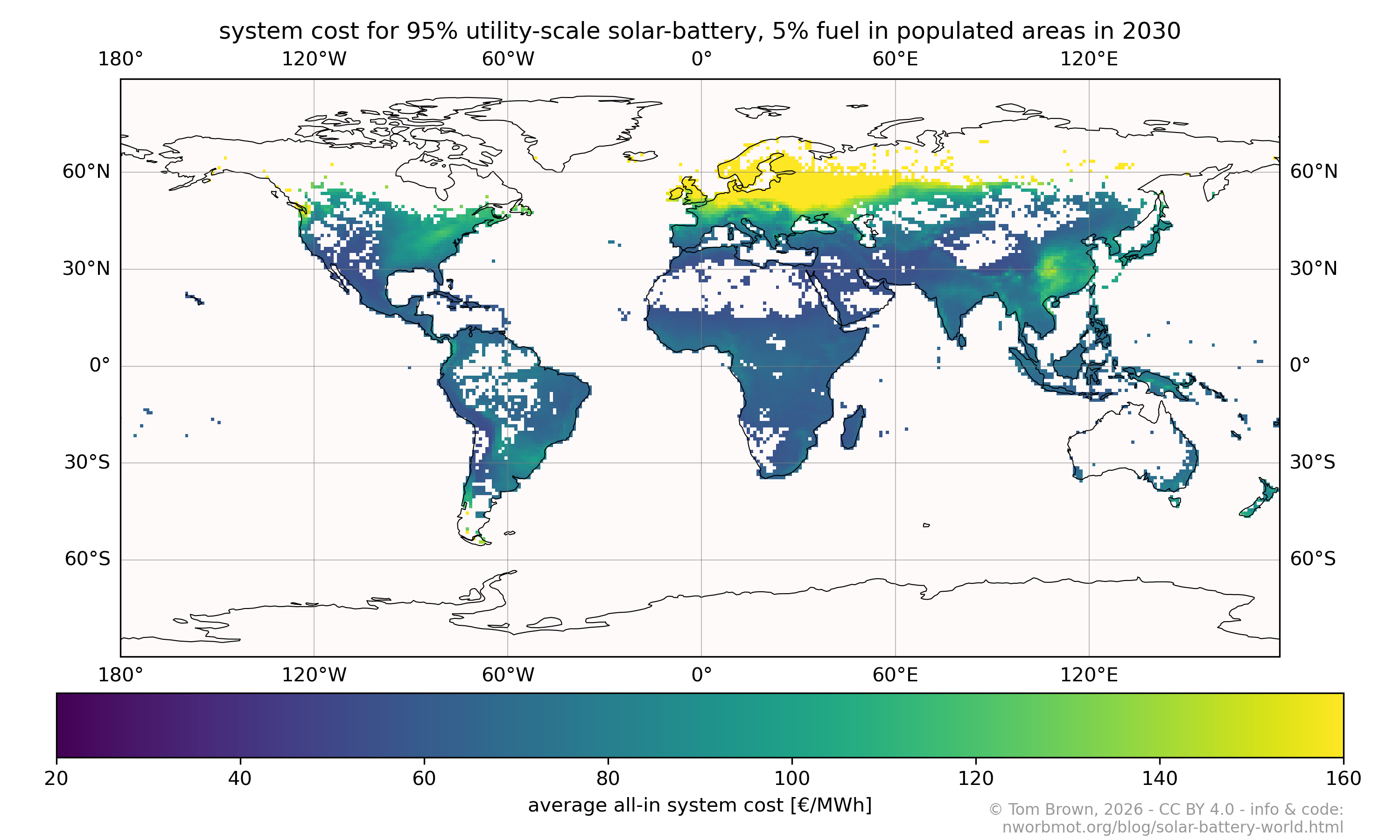

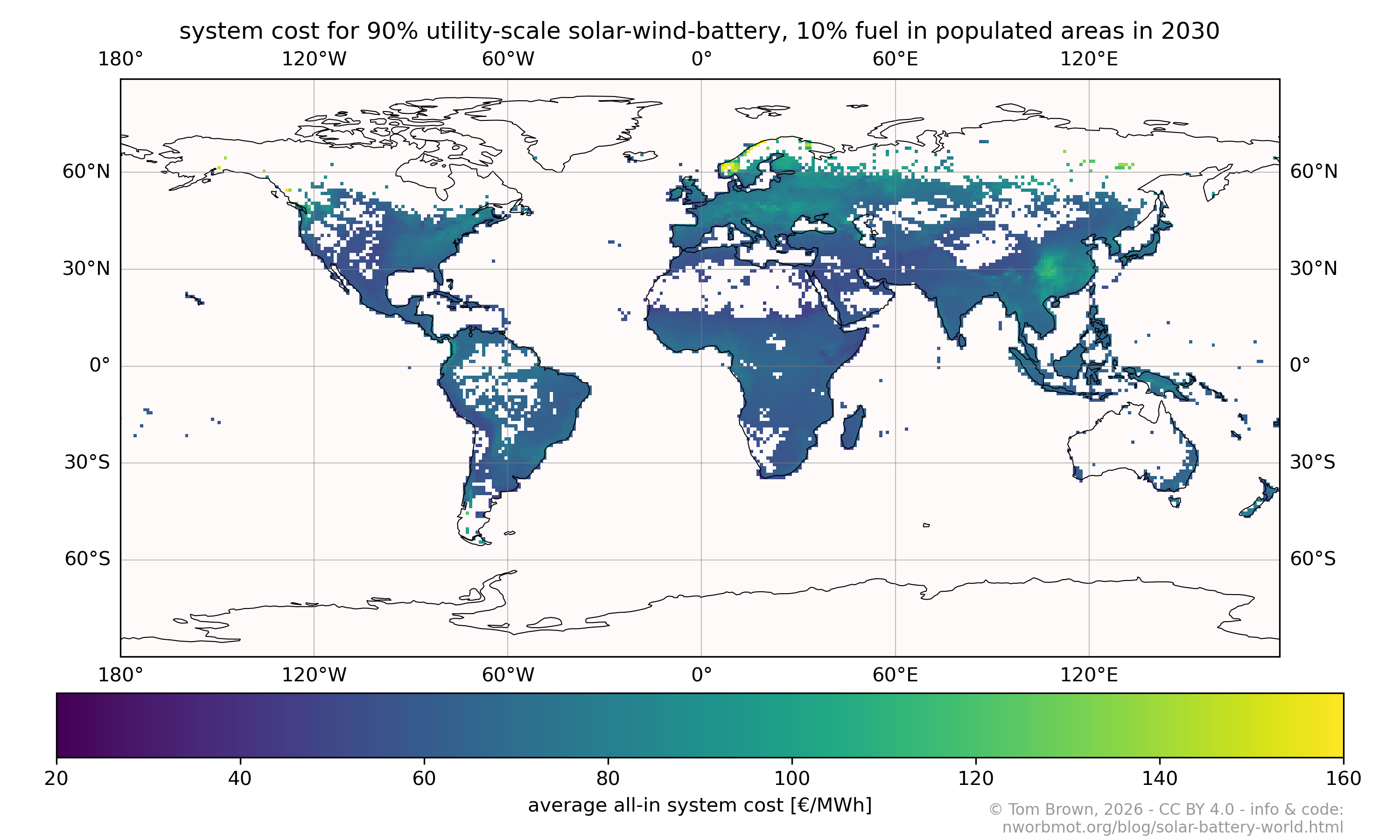

The map shows the total average system cost of providing electricity for a constant hourly demand in 2030 with solar and batteries providing 90% of the electricity and some storeable fuel the final 10%.

For 80% of the population it is below 80 €/MWh:

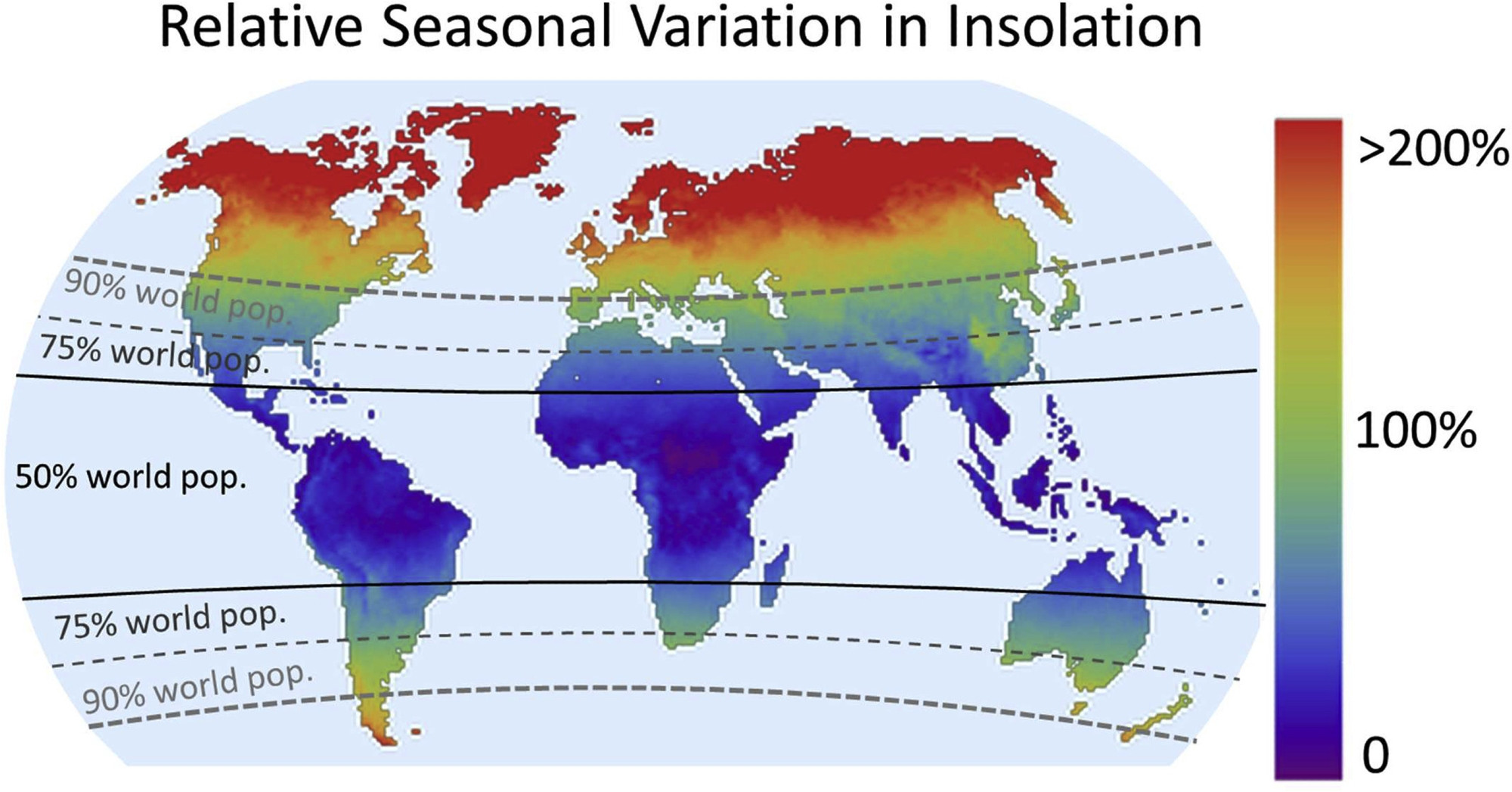

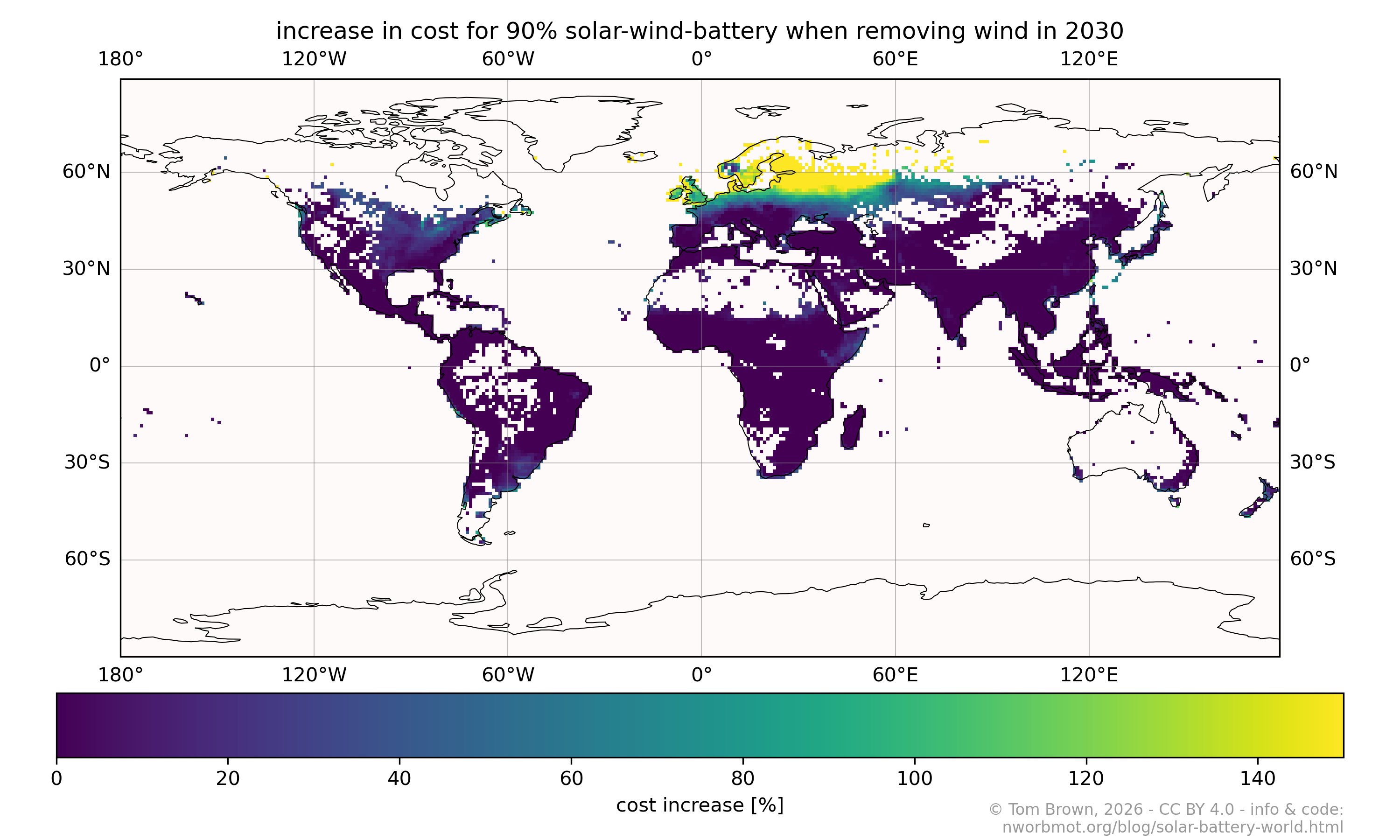

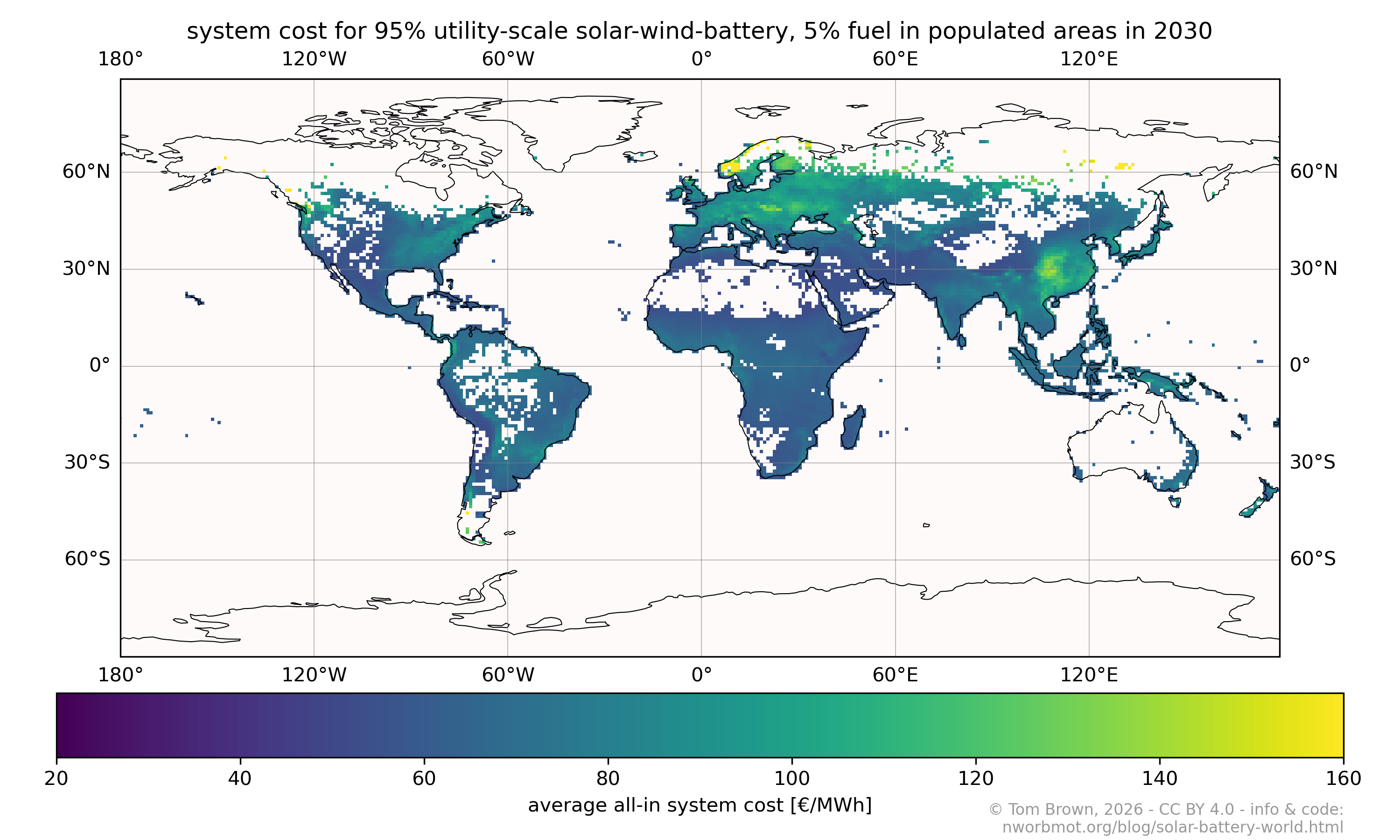

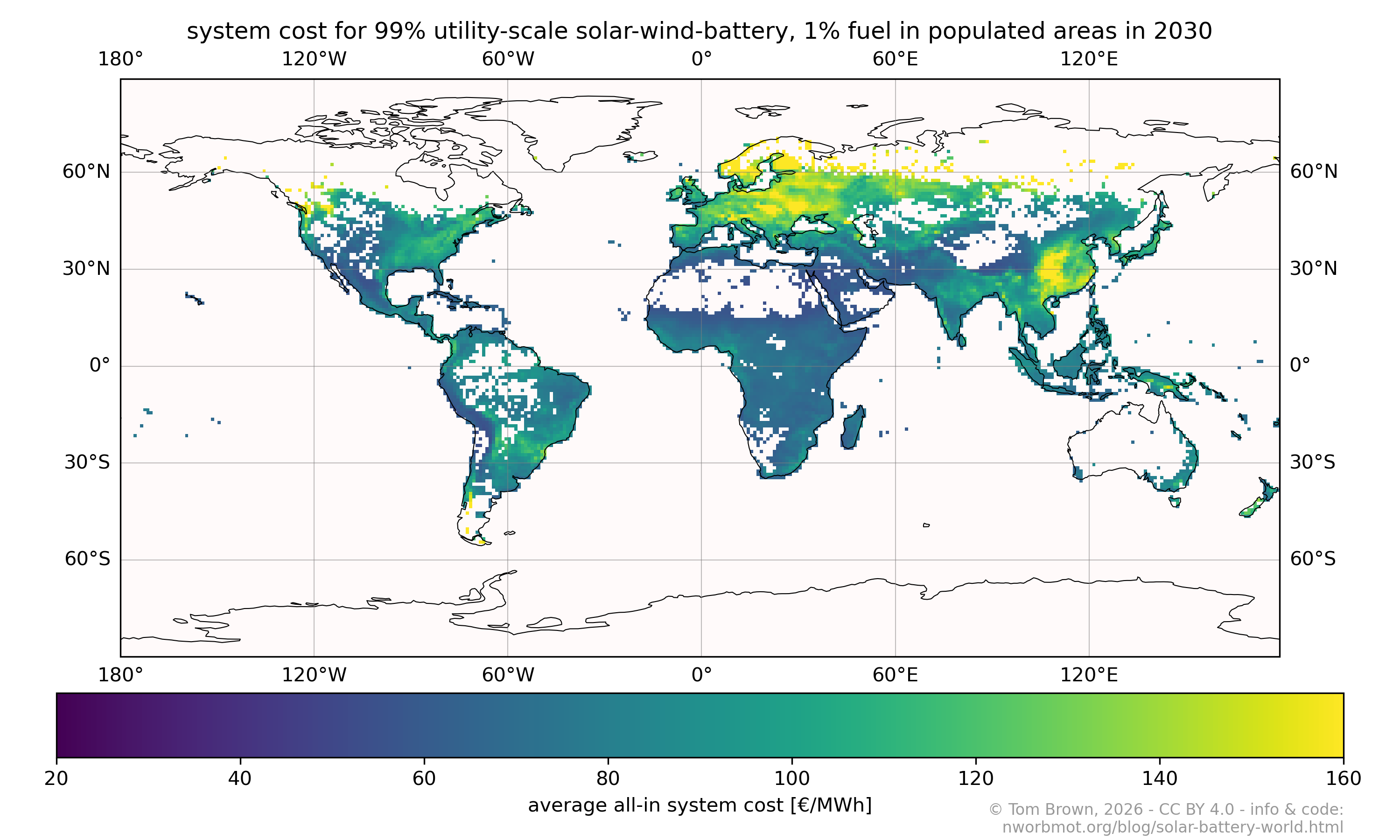

The more expensive locations are all at high latitudes in the North, where low sunshine in the winter increases backup costs. In these regions the addition of wind, existing hydro or other energy sources would help to alleviate the higher costs.

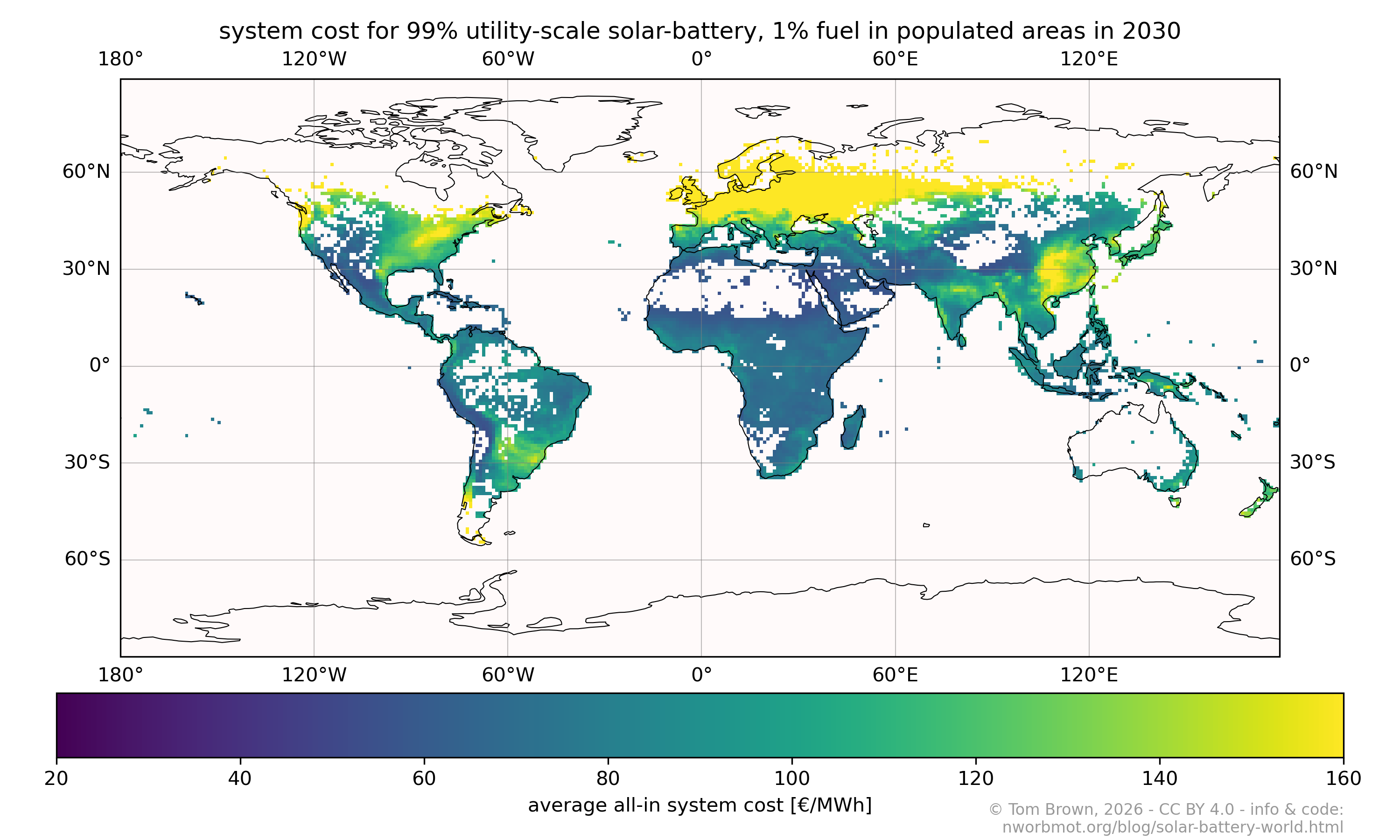

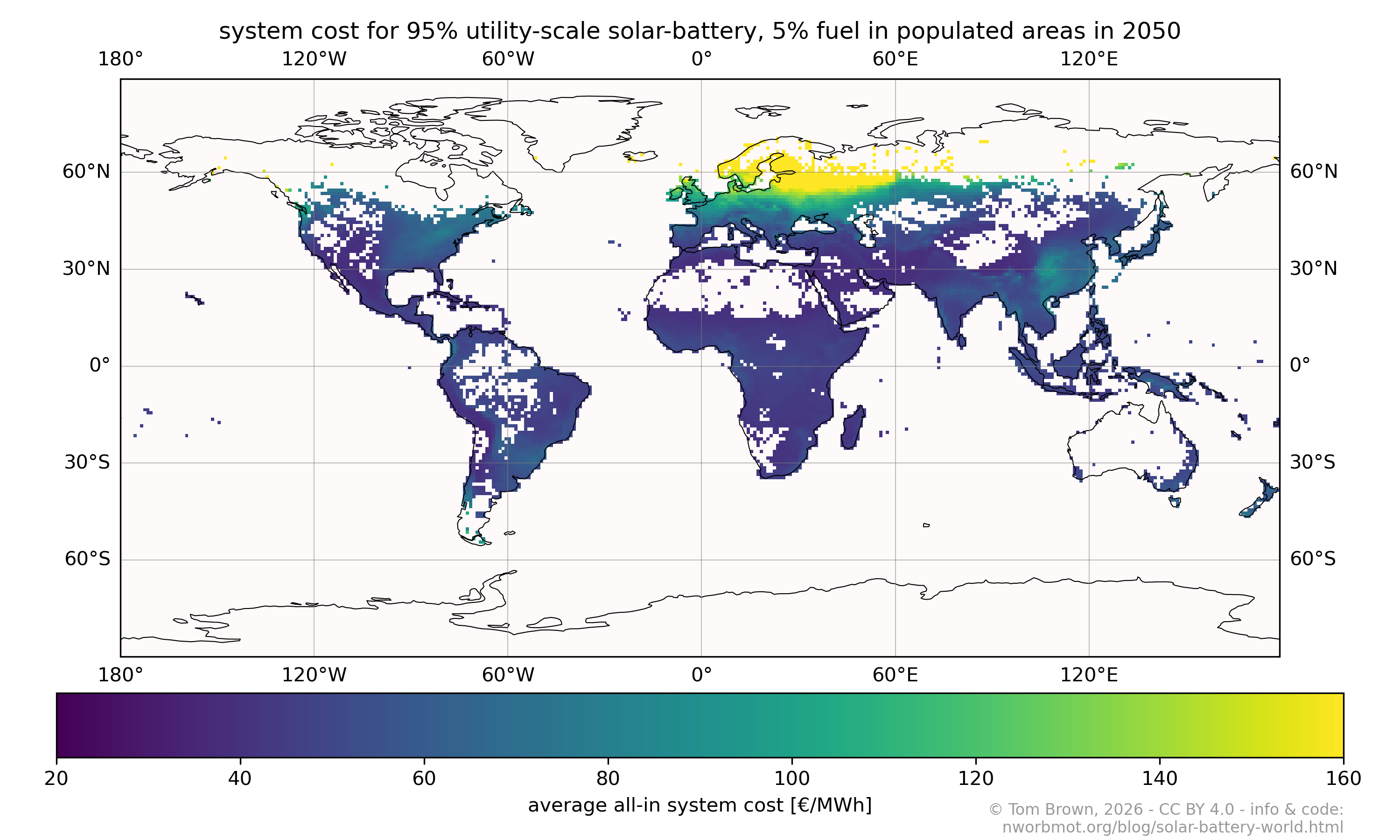

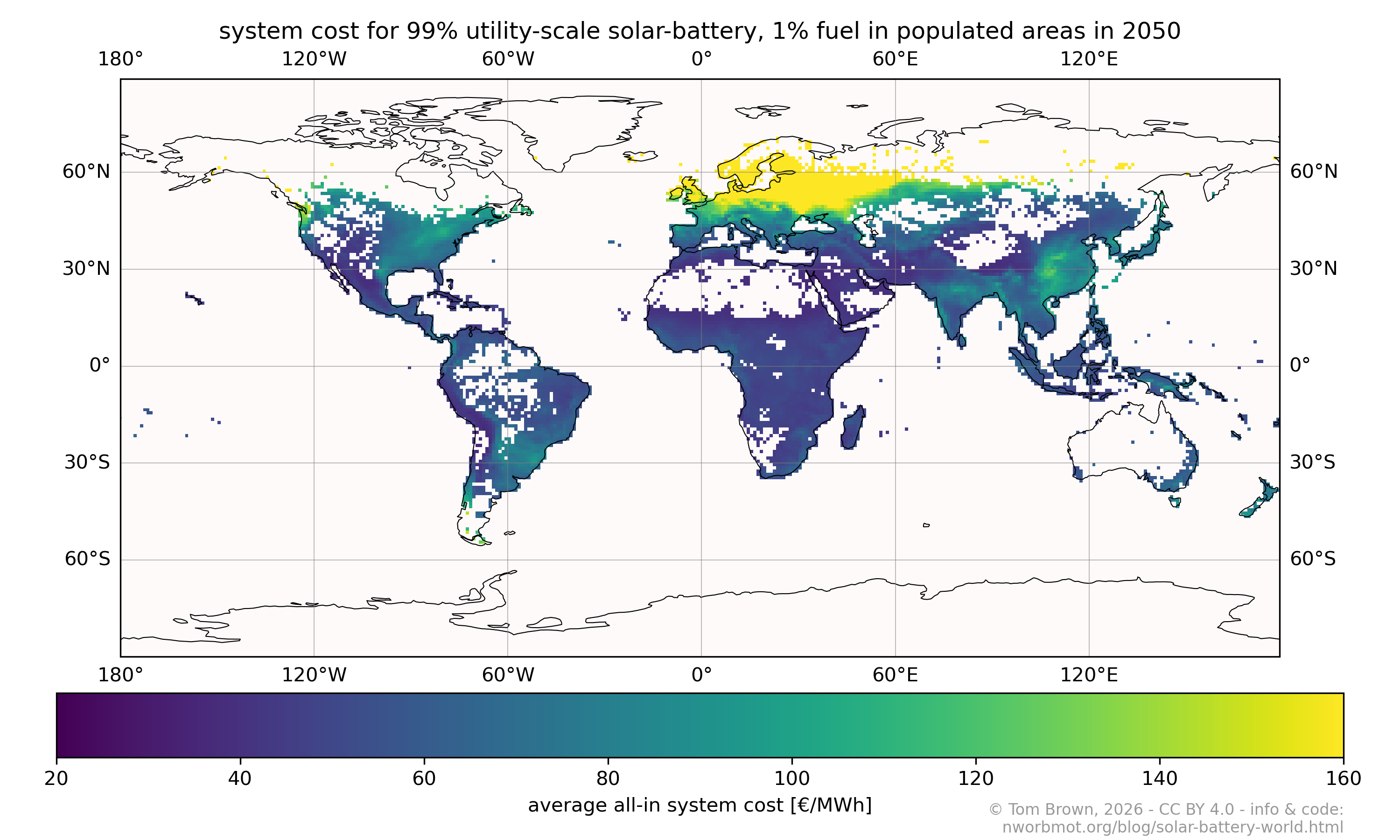

If we increase the solar-battery supply from 90% to 95% and 99%, the high-latitude regions have difficulty with the last 1-5% because of low winter sunshine.

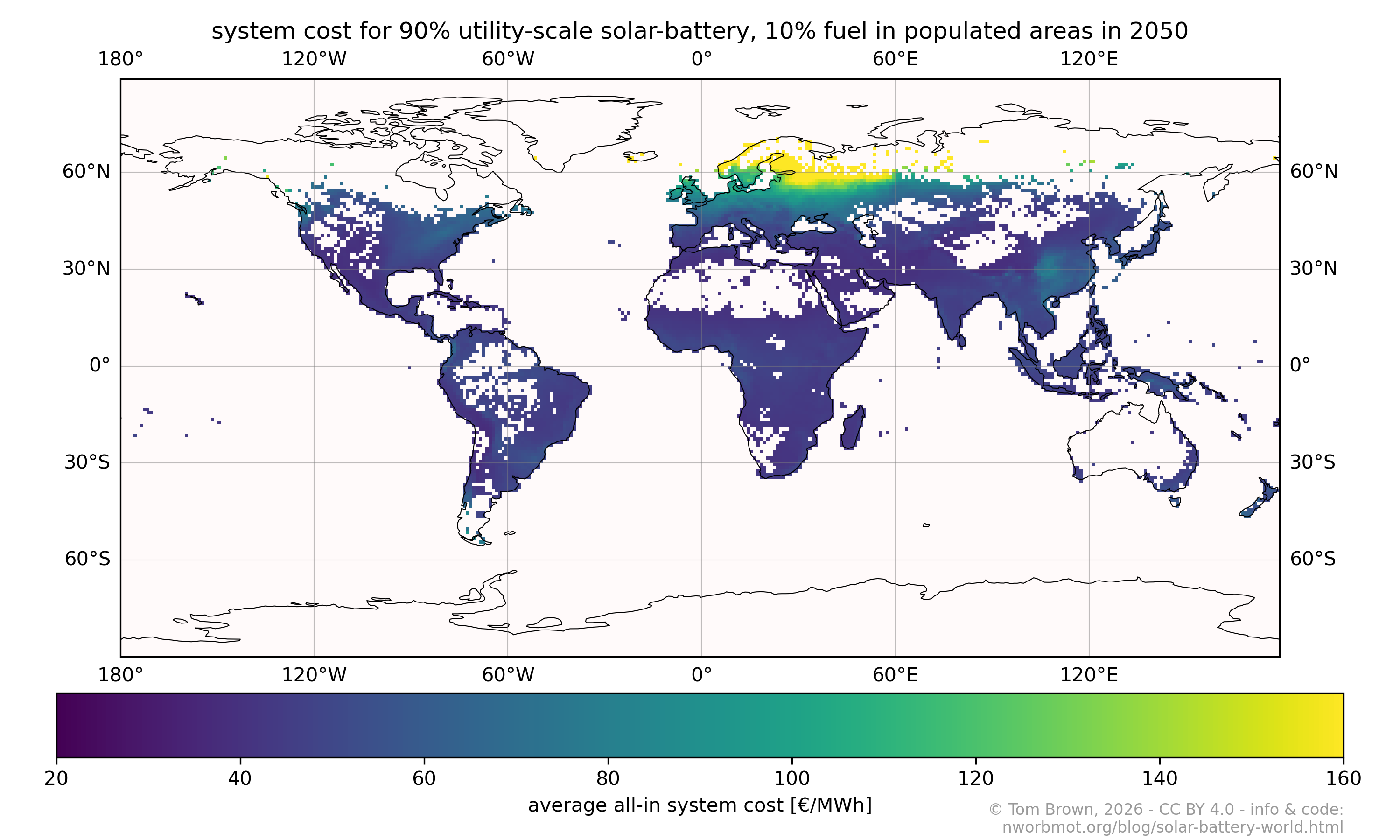

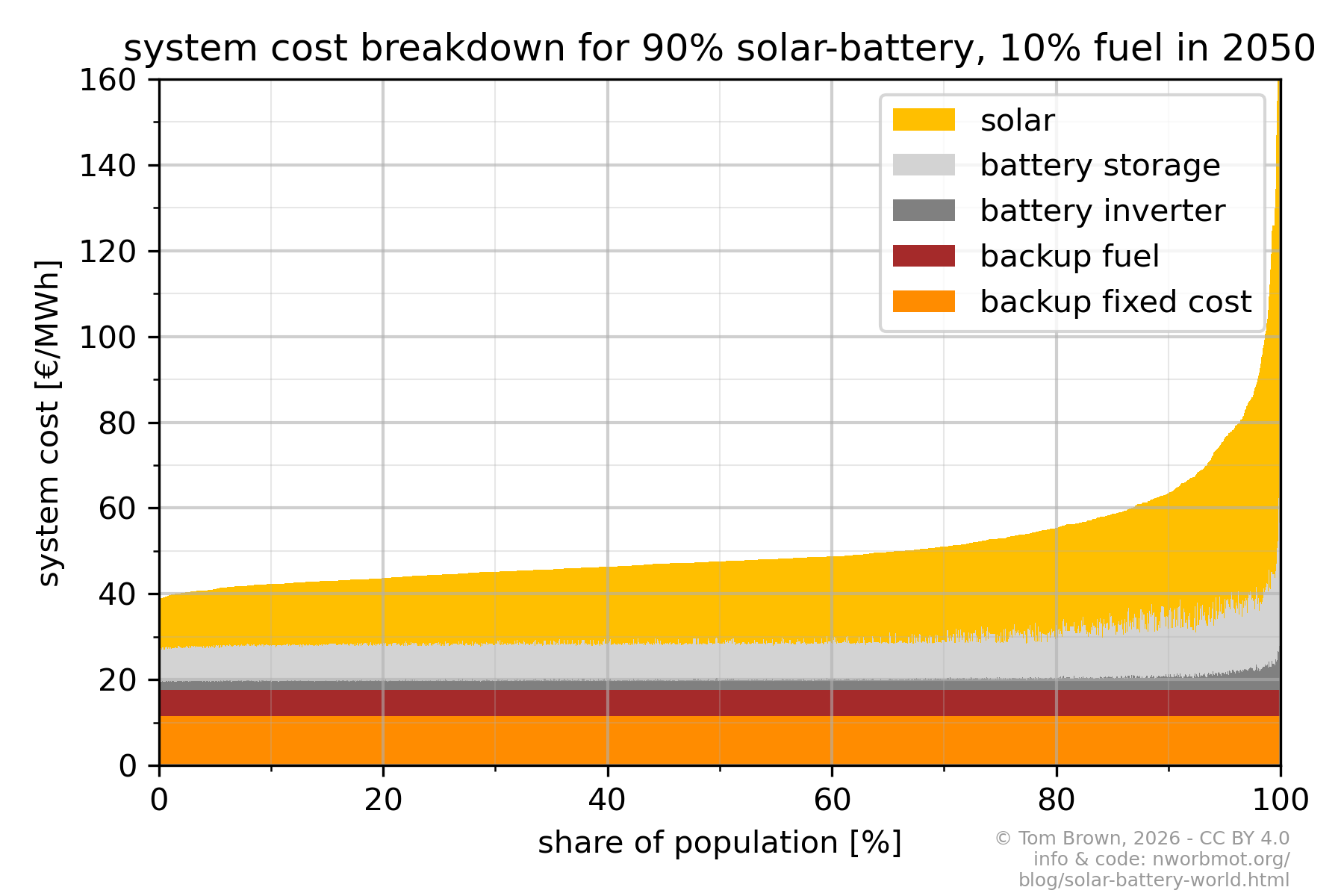

With projected cost reductions for solar and batteries in 2050, 86% of the population are below 60 €/MWh for 90% solar-battery supply, and 93% are below 80 €/MWh for 95% solar-battery supply.

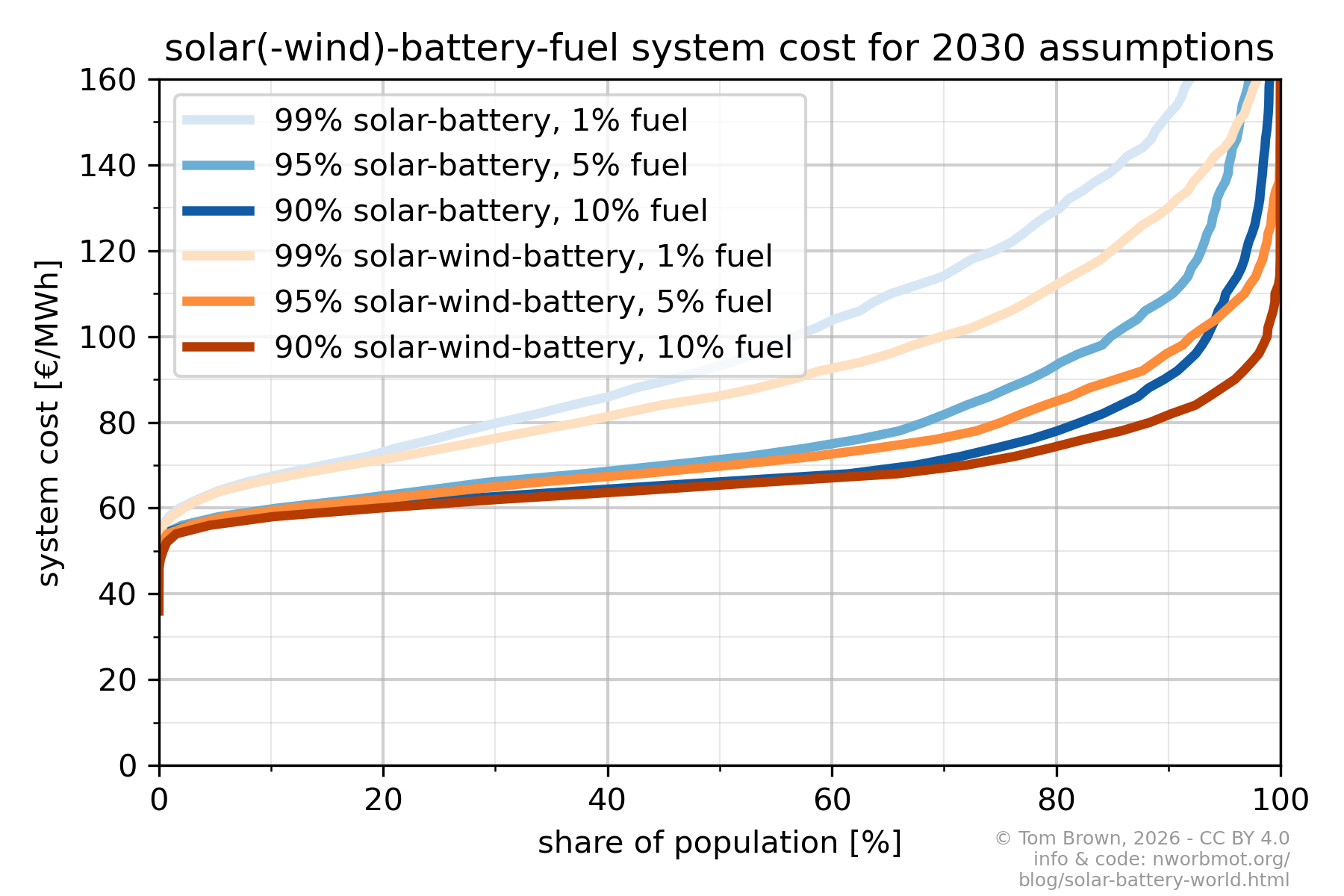

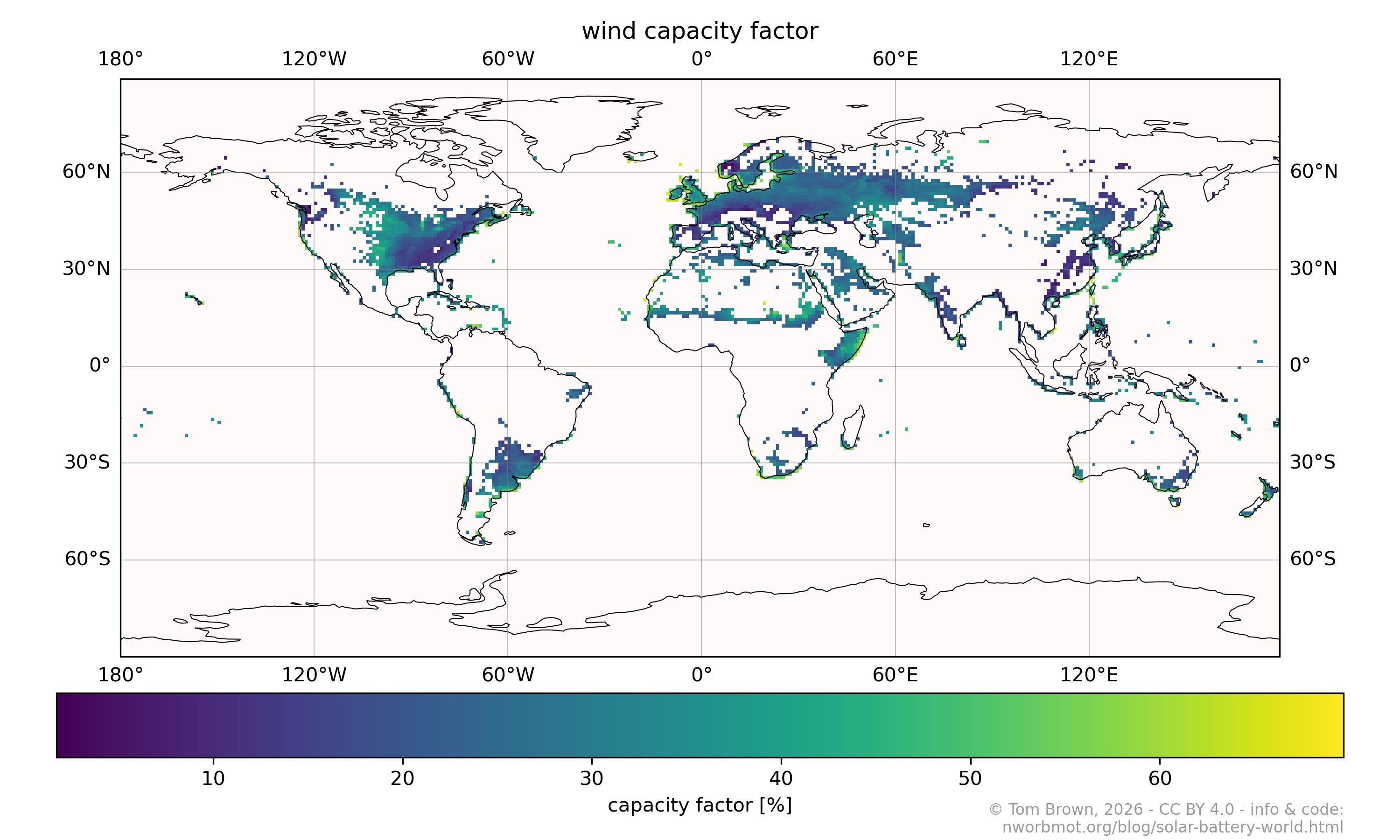

If we add wind in the case of 2030, this helps reduce costs particularly in high northern latitudes, where the wind tends to blow more strongly in the winter.

What conclusions can we draw?

- Solar and batteries have the potential to dominate electricity supply in most regions of the world, providing cheap and clean power.

- Where there is enough space, this supply can be provided close to demand (only minimal grid costs were included in these results).

- The more expensive regions are concentrated at high latitudes in the North, where seasonal variations make it attractive to include wind and other energy sources.

- We can get far without worrying about the last 5-10%. The solutions for the last 5-10% could be fossil fuels in the short-term, long-duration storage as it matures, or easily storeable e-biofuels.

Briefly on the assumptions (more below): The system cost is higher than the solar levelised cost because it also includes the costs of the batteries and backup power for the full demand, as well as accounting for curtailment. Utility-scale solar PV and batteries are sized to minimise the costs for meeting a constant demand for each of the 8760 hours in weather data from 2011. The 1° by 1° pixels are chosen based on where the population is densest, representing where 99.9% of the population lives. The model is based on model.energy but without the hydrogen storage. The most important economic data is based on the Danish Energy Agency Technology Database for 2030 in 2020 euros: solar PV installed cost 384 €/kWp, lithium-ion battery installed cost 157 €/kWh. By 2050 these reduce to 293 €/kWp and 83 €/kWh respectively. The solar costs include 50 €/kW for transformer and grid connection, but no further grid costs are included. Additional assumptions: cost of capital 5%, cost of backup generator with 50% efficiency 1000 €/kWel, cost of backup fuel (based roughly on fossil gas) 30 €/MWhth. There is more information below including instructions on how to adjust the results if you don't like the inputs.

Table of Contents

1. More technical details

The full set of technical assumptions, mostly leaning on the Danish Energy Agency Technology Database, can be found here:

https://github.com/nworbmot/solar-battery-world/blob/main/defaults.csv

As well as the incremental energy cost for the lithium-ion batteries, an inverter cost of 177 €/kW in 2030 and 66 €/kW in 2050 is also included. The lithium-ion batteries have a round-trip efficiency of 96%.

The model is based on model.energy but without the hydrogen storage. It is optimised with free backup generation for the final 10/5/1% then the costs are added back on top. This allows the user to easily increase the investment or fuel cost for the backup, since this is the most uncertain part of the costing.

To reproduce the optimisation on model.energy, choose the point location in "Step 1". Then for the technologies in "Step 3", disable wind and hydrogen storage. Under "Advanced settings" enable the checkbox for "Dispatchable technology 1" and set both its overnight cost and marginal cost to zero. To get (100-x)% solar-battery coverage, i.e. limit the backup to x% coverage, put a dummy emissions factor of 100 gCO2/kWhel on the backup, and then activate the checkbox for the overall CO2 limit and set the allowed emissions to x gCO2/kWhel. The CO2 emissions limit is being used as a proxy for the overall backup fuel usage.

Once you have the optimisation result, you can add the backup costs separately. For example, if the solar-battery system on its own costs 50 €/MWh for (100-x)% coverage, where x=10,5,1, then you add for the backup per €/MWh (assuming enough backup capacity to cover the entire load):

investment cost * (annuity factor + FOM) / 8760 + fuel cost * x / efficiency

For the default back investment cost of 1 M€/MW, 25 year lifetime, 5% cost of capital, 3% yearly FOM, fuel cost of 30 €/MWhth, efficiency 50% you get

1e6 * (0.071 + 0.03) / 8760 + 30*(x/100)/0.5 = (11.5 + 0.6x) €/MWh

If the investment cost rises to 2 M€/MW, the fixed part rises from 11.5 €/MWh to 23 €/MWh.

For x=10 with the original settings, you get a total 17.5 €/MWh contribution from the backup.

If the fuel cost rises from 30 €/MWh to 50 €/MWh, the backup contribution rises to (11.5 + x) = 21.5 €/MWh.

The sensitivity of the total cost to the fuel cost is directly tied to x - the more solar and wind, the lower x and the less the fuel dependency becomes.

To supply the full demand with these assumptions with a fuel cost of 30 €/MWhth would cost (11.5 + 60) = 71.5 €/MWh, which is more expensive in most locations that the solar-battery-fuel system. However the cost of the backup fuel will vary by location based on availability.

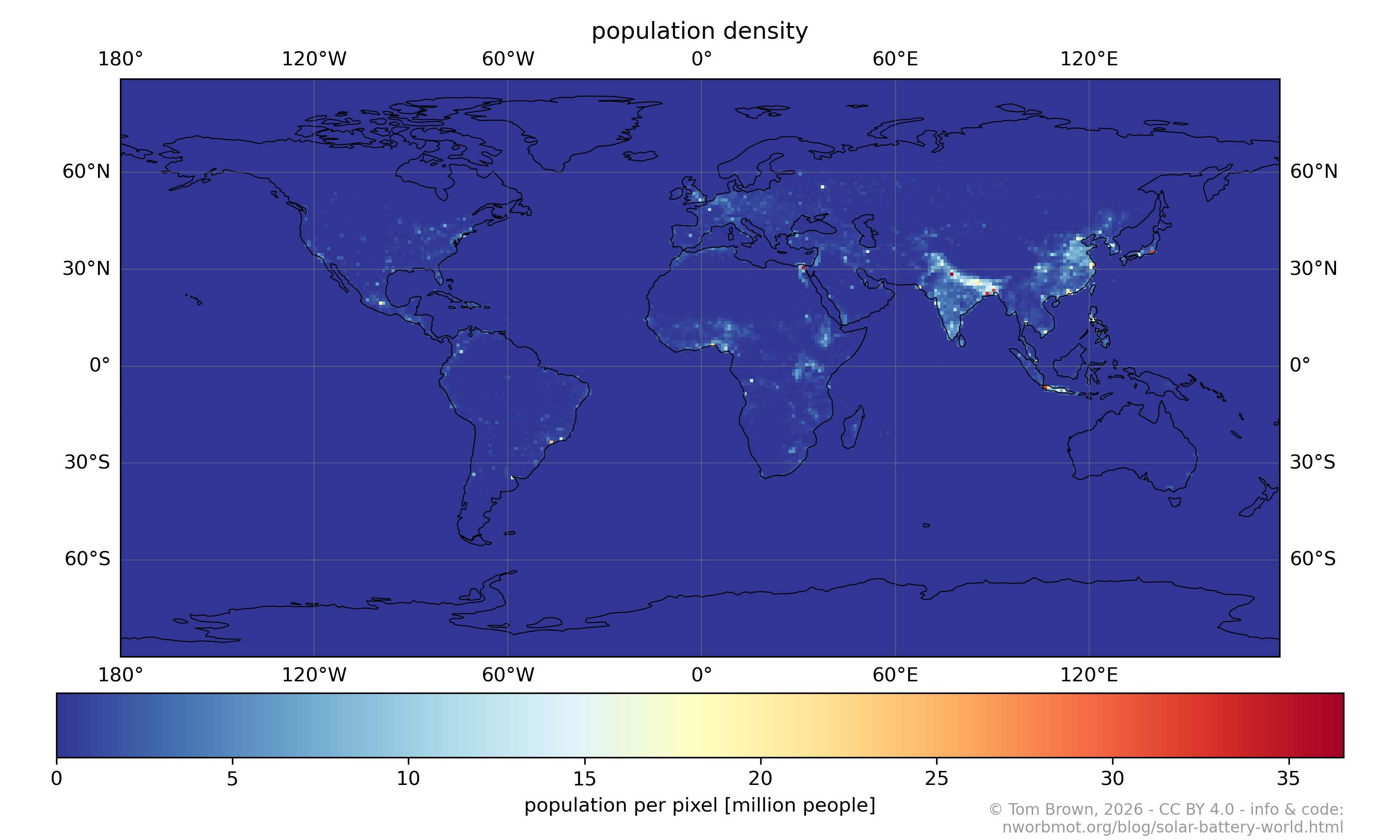

The calculations are carried out for the 9196 1° by 1° pixels that contains more than 10,000 people, which is enough to include 99.86% of the population.

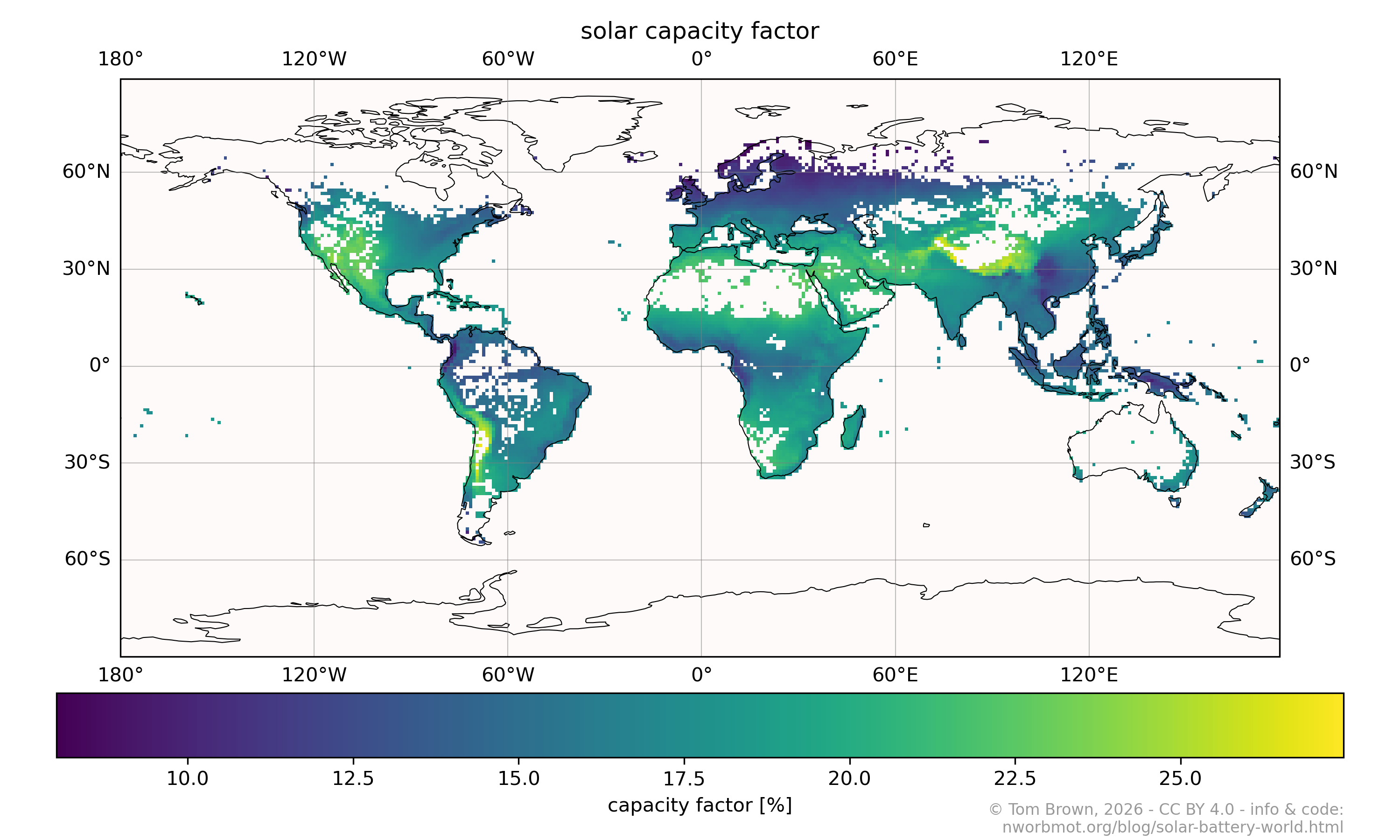

Here are the capacity factors (average production divided by capacity) for solar and wind, at the locations where they are built by the model:

The setup is somewhat similar to a 2025 Ember report, but whereas they fixed the solar and battery capacities relative to a constant demand, and varied the location, we fix instead the fraction of load supplied, and optimise the solar and battery capacities.

Victoria et al, 2021 also pointed out the coincidence of low seasonal solar variation and the locations where most of the population lives in this nice graphic:

2. Warnings

Many of the model.energy warnings also apply here.

- The demand is flat, so doesn't account for seasonal variability in demand. Cooling demand align well with solar insolation. However, seasonal heating demands can be a challenge for solar-based systems. For high latitudes in the North, the wind is stronger in the winter, which raises the value of including wind.

- The more technologies we include, the cheaper the supply cost can become. In particular more storage technologies, wind, existing hydro and other low-carbon sources can decrease costs while keeping emissions low.

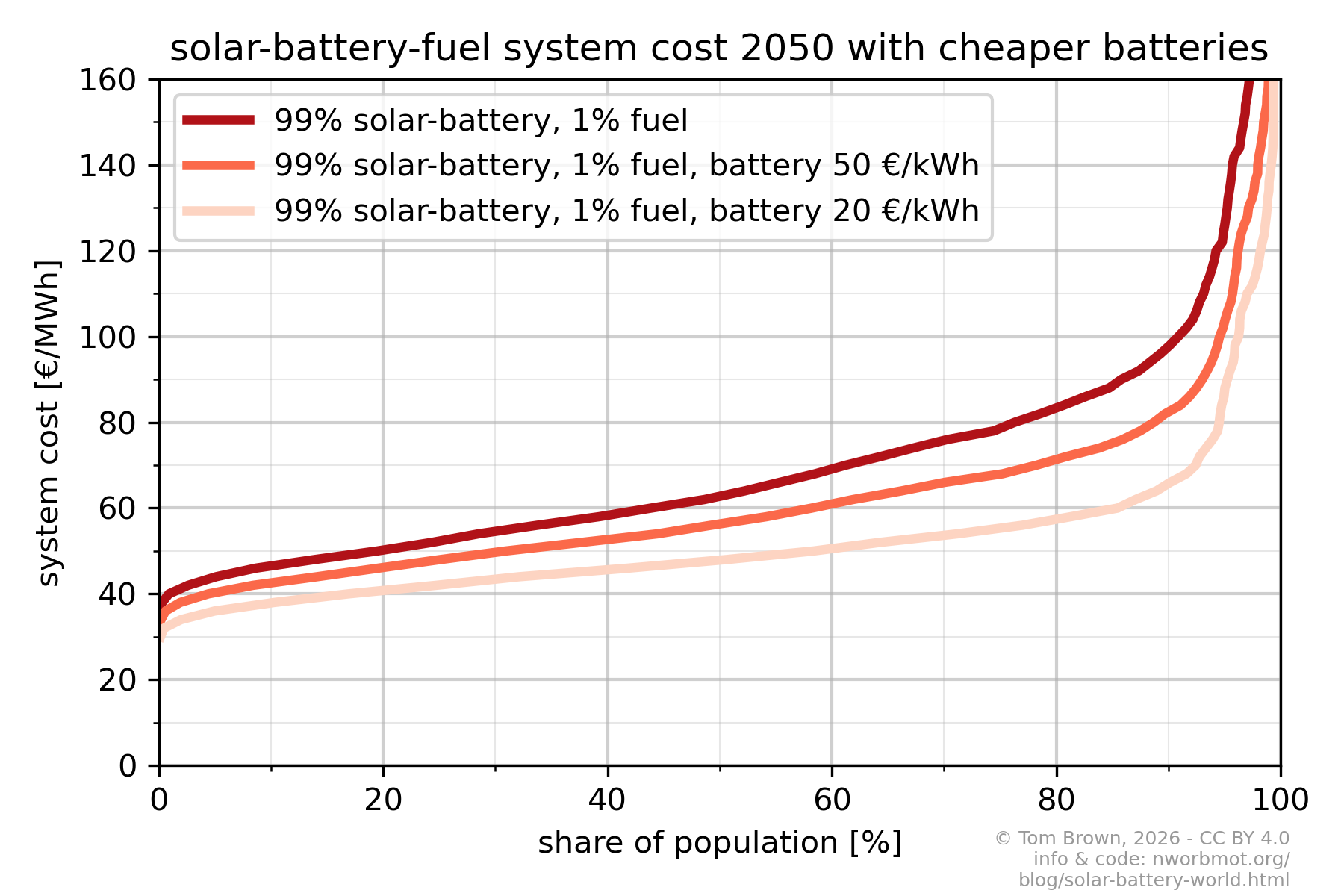

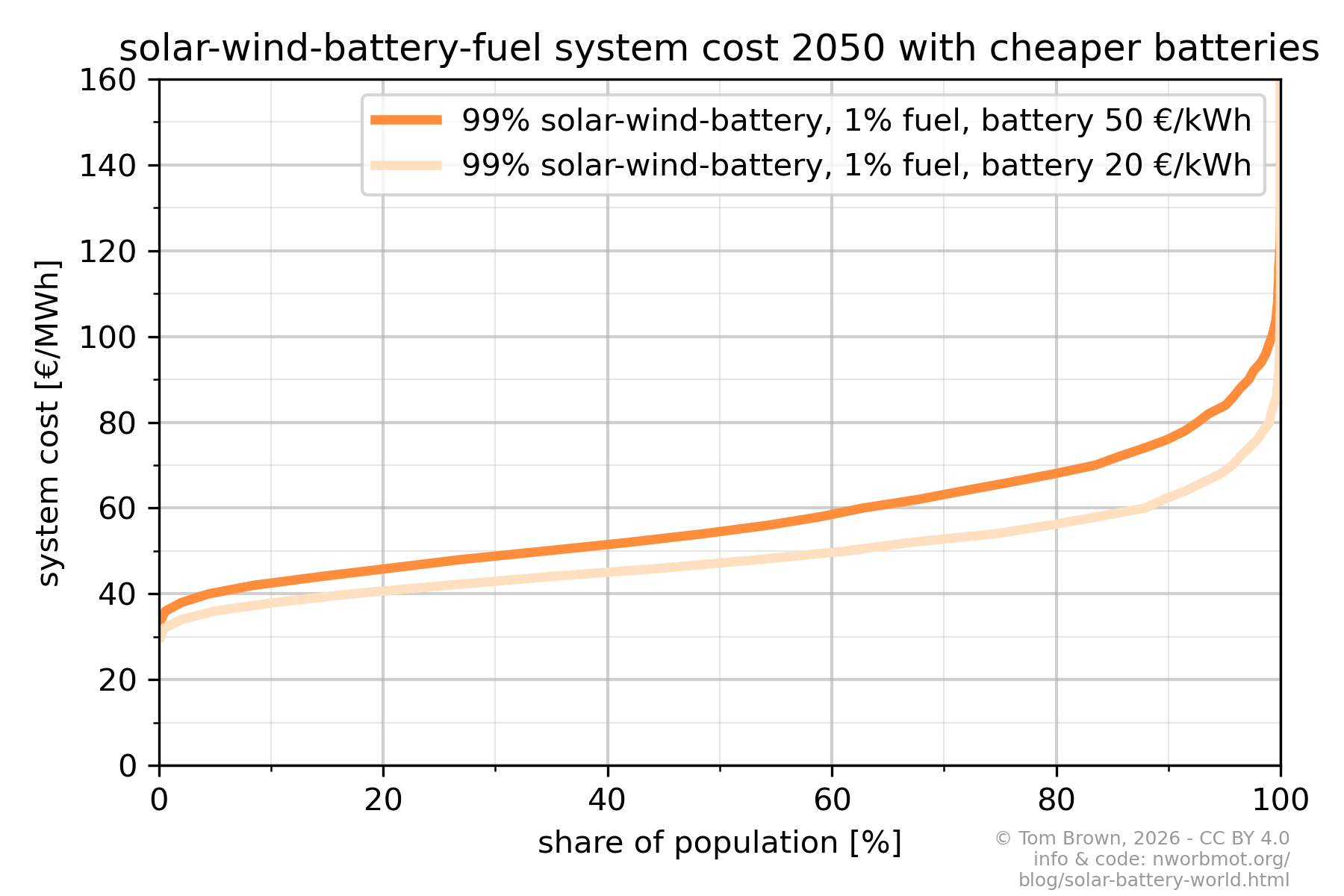

- The results are quite sensitive to battery costs, so further cost reductions here could bring the system costs down further.

- The results are based on today's population distribution. Since population is growing faster at lower latitudes, the fraction of the population with low cost will only increase.

- Electricity demand doesn't necessarily follow population demand. Data centres and other electricity-intensive industries may relocate to cheaper locations.

- Including demand response, such as from battery electric vehicles, can further reduce costs.

- Connecting regions can also spread balancing costs, particularly for wind-heavy systems, at the expense of building the necessary grid infrastructure.

- General grid costs were not included here beyond 50 €/kW to connect the solar, because in principle these utility-scale systems could be implemented locally if there is space, and distribution costs will vary from region to region.

- The solar panels have a fixed tilt of 35 degrees towards the equator. Axis-tracking could lower costs.

- The cost assumptions assume utility-scale solar panels and batteries in large parks. Smaller-scale rooftop solar and home batteries would cost 2-3 times more.

- There may not be sufficient land near densely-populated areas. This may require supply from further away. More discussion on land use can be found below.

- The cost of capital, assumed to be 5%, may be higher in some regions.

- The solar insolation is based on reanalysis data from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ERA5 dataset and is processed using the atlite library. Reanalysis data is sometimes imperfect.

3. Open code and data

All code on which these calculations are based is available with an open licence:

https://github.com/nworbmot/solar-battery-world

Outputs from the scenarios are also available with an open licence:

4. Land and material use

Some rough calculations are provided here.

Assuming most energy demand electrifies and living standards equalise worldwide, each person would consume annually around 10 MWhel/a/person.

This gives worldwide electricity demand for 8 billion people of 80,000 TWhel/a.

The 90% solar-battery supply would require then 69 TWp of solar and 72 TWh of batteries in 2050.

70 TWp at 50 MWp/km2 covers 1,400,000 km2, around 1% of total land and 3.7% of land used for livestock:

But locally in densely-populated areas there may not be sufficient land, requiring the grid to transport it from neighbouring regions.

5. Additional results

5.1. Additional plots for main 90% solar-battery scenario

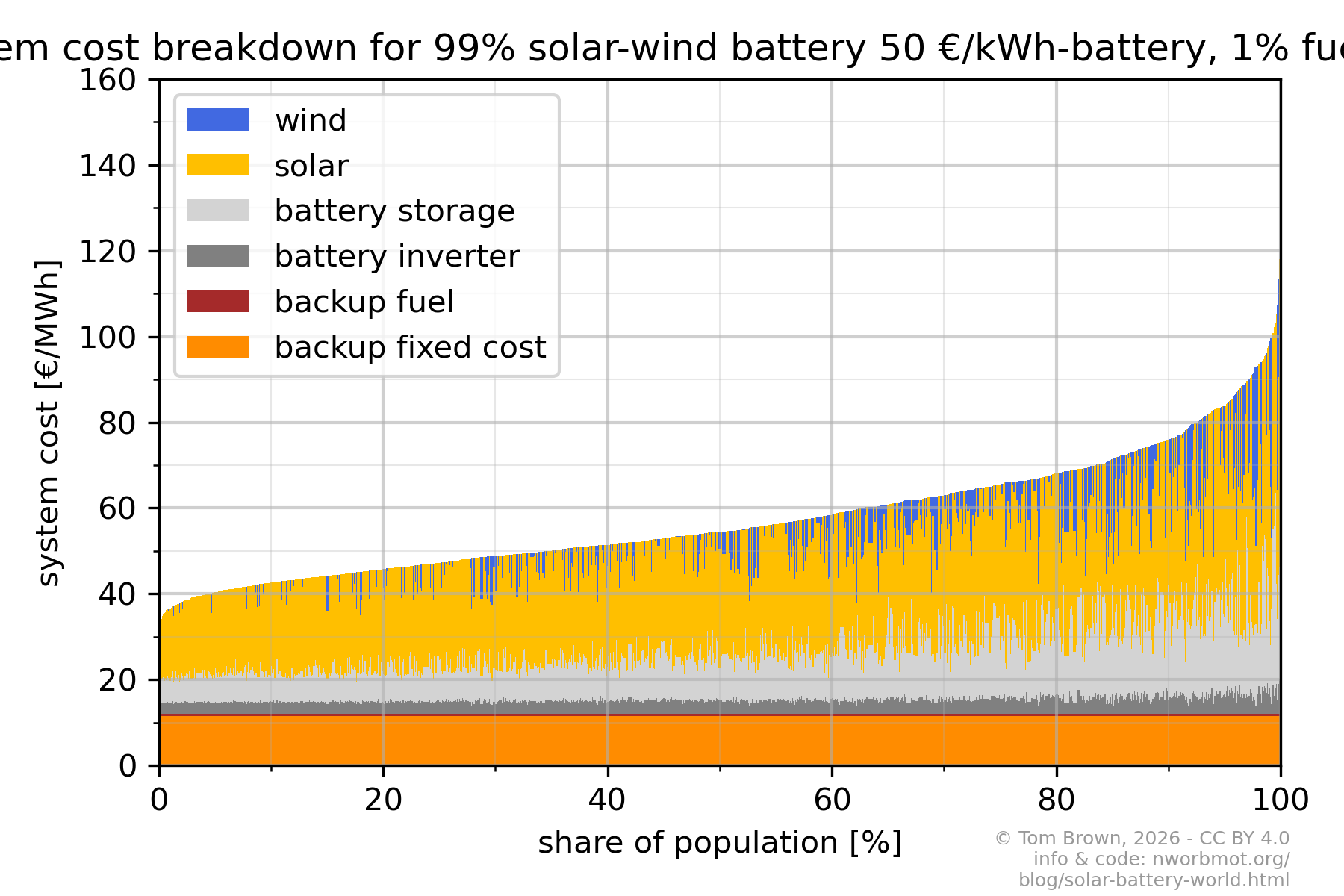

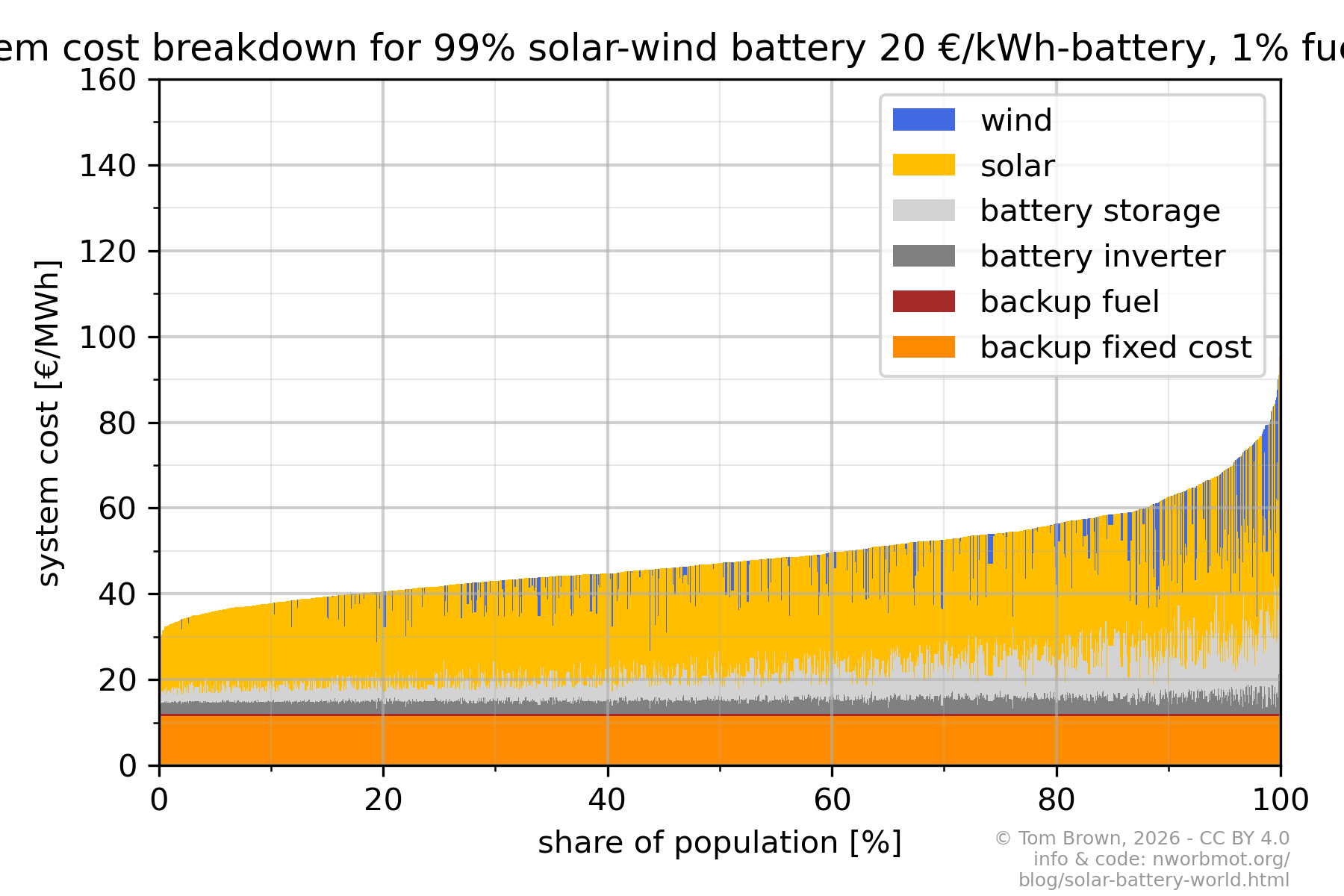

5.2. 2050 results with battery investment cost reduced from 83 to 50 and 20 €/kWh

The default battery installed cost assumption for 2050 is 83 €/kWh. Utility-scale sodium-ion batteries could drop to 29-52 €/kWh according to Keiner et al, 2025, so we also provide here some simulations with lower-cost batteries.

5.3. 2030 cost increase for solar-wind-battery when removing wind

5.4. Maps of other scenarios

5.4.1. 2030 solar-battery

5.4.2. 2050 solar-battery

5.4.3. 2030 solar-wind-battery

5.5. Stacked costs for other scenarios

5.5.1. 2050 90% solar-battery

5.5.2. 2030 90% solar-wind-battery

5.5.3. 2050 99% solar-wind-battery with cheaper batteries